Forensic and Therapeutic Roles

What is the difference between therapy and a forensic evaluation?

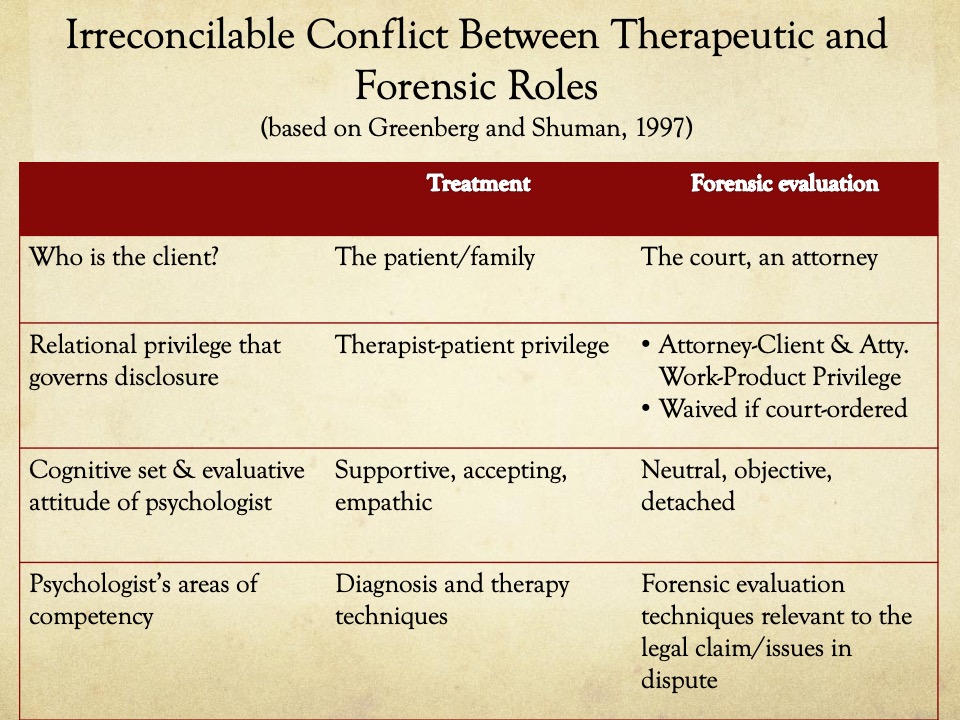

Greenberg and Shuman wrote the classic article on the difference between the role of treating expert versus the role of forensic expert. They titled this article “Irreconcilable Conflict between Therapeutic and Forensic Roles” which pretty much sums up their opinion on the topic

According to Greenberg and Shuman, all therapy is based on the following principles:

1. Maintaining a positive rapport between the therapist and the patient

2. Encouraging free expression of thoughts and feelings by the patient

3. We are trained to accept, support and advocate for our patient’s needs

4. In general, we assume that our patients provide us, or attempt to provide us with accurate information, because that will help them

We generally work within the patient’s perceptions of their outside world rather than attempting to determine the factual accuracy of these perceptions through other methods of gaining information (e.g.,, reviewing court, police or medical records, collateral contacts)

- Our ethical obligation is to the patient, not to some authority, such as the court, or to an attorney who hires us.

• A forensic expert needs to be objective, never caught in a conflict between giving the court reliable and impartial information versus harming the patient’s interest.

2. Similarly, our preexisting relationship with our patient interferes with our objectivity, impartiality and may harm the legitimate interests of other persons. All communications with the patient are privileged, confidential.

• In a forensic context there is no therapist-patient privilege, and the patient must be informed of this.

3. In therapy, we are supportive, accepting and empathic in our attitude.

• The attitude and cognitive set of the forensic expert is very different from that of the therapist: neutral, objective, and detached.

4. The techniques we use are intended to help us understand our patient in depth and to realizing their goals.

• In contrast, when we are retained by the court or by an attorney, none of these assumptions apply:

• Our primary obligation is to the court who appointed us, or in adversarial proceedings, to the party who retained

our services.

• Clearly we have ethical obligations to the person being evaluated as well: competence, absence of conflicts of

interest, informed consent, objectivity, adequate assessment, and integrity.

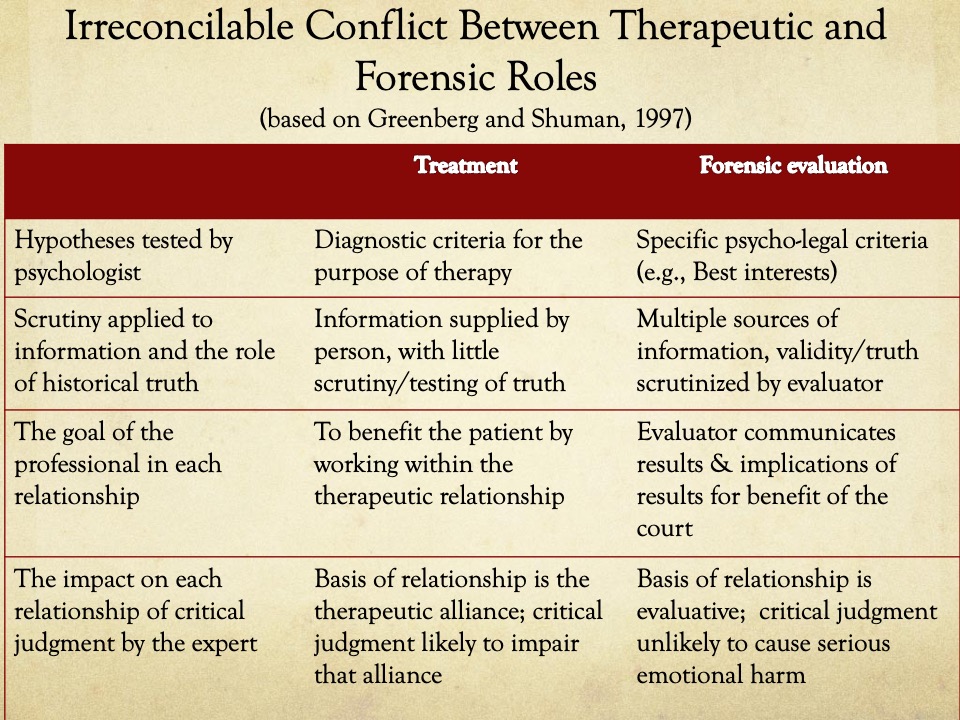

Greenberg and Shuman argue that the type of information typically gained in therapy is not adequate for the court’s expectation that an expert opinion is reliable and valid to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty. They argue convincingly that a role conflict occurs when a person who has been retained as a therapist also offers opinions on the psycho-legal issues.

Greenberg and Shuman: “Forensic psychologists realize that their public role as ‘expert to the court’ or as ‘expert representing the profession’ confers upon them a special responsibility for fairness and accuracy.”

Example: A mother tells a CIT that the child’s father was emotionally and physically abusive to her during the marriage, and was emotionally abusive to the child, frightening the boy by yelling at him and mom, telling him scary stories and playing scary games with the child. The child confirms mother’s descriptions, saying that the dad has repeatedly scared him. So, in this example :

A. What kinds of hypotheses are we working with as we listen to this lady?

1. In therapy, we adopt hypotheses about the patient’s history for the purpose of treatment, but these are provisional, and subject to change.

– We might assume that the patient’s anxiety is caused by her husband’s alleged behavior, but the CIT must be open to the possibility that this assumption could be wrong.

2. In a forensic setting our conclusions have to address the legal issues in the case, and have to be based on a reasonable degree of psychological certainty or probability.

– Our procedures for reaching these conclusions have to be valid and reliable, and generally accepted by our profession. We must not make reach conclusions based upon assumptions or guesses

B. How do we test the truth of the hypothesis that the husband’s behavior has led to the patient’s anxiety about her child?

1. In a therapeutic context we look for coherence in the narrative she presents or other signs of truth-telling, e.g., affect and defenses which are appropriate to her experiences.

– We focus on her symptoms. and those of the child– are they consistent with her statements?

– If a psychological evaluation has been performed, we would look for its consistency with our hypotheses.

2. In a forensic evaluation, we look for corroborating factual information: e.g., doctors and hospital records, persons she informed about the alleged abuse, clinical and test evidence consistent with PTSD.

– Our approach would be cautious, always with an eye on what we don’t know with reasonable certainty.

– We would scrutinize alternative explanations and weigh the evidence supporting each one.

C. What is the goal of our involvement with the person being evaluated or treated?

1. In treatment our goal is to benefit the patient therapeutically. Other goals are likely to conflict with achieving this goal.

2. In a forensic context such as an evaluator for the family court our goal is to assist the court in making its decisions by providing reasonably objective and unbiased conclusions

D. Can we reach judgments or conclusions that are critical of this mother?

1. In treatment, the basis of our relationship is to enhance the patient’s functioning: although we may confront self-destructive behavior, we avoid making critical judgments, for the sake of the therapeutic alliance, maintaining empathic attunement and facilitating growth.

2. In a forensic context, critical judgments are expected of us, when they are justified. The best interests of the children, for example, are not necessarily the best interests of their parents. So while a therapist may see his obligation as supporting his client’s self-esteem, showing empathy for her plight, helping her to achieve her goals, the forensic expert is more concerned with the validity of his or her conclusions, and can not be nearly so concerned with the patient’s potential feelings of frustration, hurt and anger as the expert makes judgments.