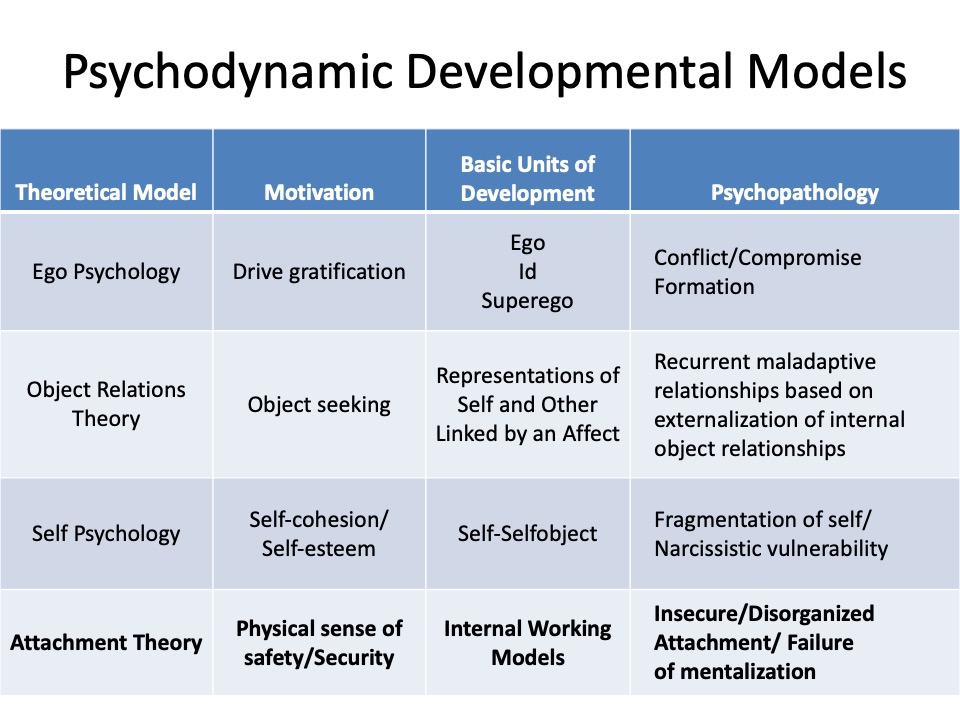

Bowlby’s attachment theory revolutionized psychodynamic theory & therapy. The relational genesis and restoration of the self, of self-regulation and attachments through therapy will be explored, from its roots in psychodynamic theory to modern relational, self-psychology and interpersonal models of psychotherapy.

John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth are the founders of Attachment Theory:

John Bowlby

John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist originally trained as a psychoanalyst, rejected the traditional explanation that the infant’s attachment to the parent (mother) was a secondary drive, based upon the gratification of oral needs (Freud’s “anaclitic” theory of attachment). In Freud’s view, the mother became important to the infant only because of her role as a need-satisfying ‘object’ of a physical need (drive). Her role as an object of love (attachment) was secondary to her being the object of (oral) drive-gratification.

For Bowlby, and modern psychodynamic thinkers, the bond with an attachment figure is primary, ‘instinctual,’ not acquired, in the sense that the infant is biologically predisposed to bond, seek proximity to and love an attachment figure. All mammals, and many other species, develop an attachment, for good biological (survival) reasons.

Bowlby early on observed that many of his child and adolescent patients had histories of deprivation of maternal care and separations from their mothers. He later (with James Robertson) studied children separated from their families in hospitals and during the WWII ‘blitz.’

For Sigmund Freud the ultimate explanation of psychological processes and problems was drives, which came in two classes: Libido, and Aggression. Drive, per Freud is “a demand made upon the mind for work,” a demand which comes from the body. This was Freud’s metapsychology: an explanatory framework for all psychic phenomena: the dynamic [drives, Libido and Aggression], economic [energy], structural [id, ego, superego], topographical [conscious/unconscious], developmental, and adaptive points of view.

According to Freud and his students, Libido originates in the Id and is the life-preservative (as well as sexual) instinct. Aggression also originates in the id, and is the destructive (aggressive) instinct. Libido and aggression are the sources of energy (drive) motivating action, thought, and emotion. Emotion includes pleasure and its opposite, anxiety, guilt, shame, concern, affection, and love. Freud also focused on internal representations of significant others, which he called internal objects. These internal objects form the basis for relationships (attachments), transferences to the analyst, and the interpersonal and intrapsychic conflicts, ambivalence towards objects and complications in relationships (e.g., the Oedipus Complex). Internal representations are cathected with libinal and aggressive emotions. Libido, aggression, emotions, and internal representations develop over the course of normal childhood and adolescent development. Freud’s student, Erik Erikson, studied the development of adults, as well as children.

Unfortunately, for over 30 years the work of Bowlby was either ignored, or actively criticized by psychoanalytic thinkers and practitioners (cf. Slade, 1999 and 2018, Fonagy et. al. 2018). In part this was due to dogmatism and inflexibility, because Bowlby’s emphasis on evolutionary, non-drive explanations of attachment contradicted Freud’s ‘metapsychology’ of drives

British Object Relations theorists, like W.R.D. Fairbairn and D.W. Winnicott, believed that libido is essentially the desire to be connected to others.

For Fairbairn “The ego, and therefore libido, is fundamentally object-seeking…”; i.e., behavior is driven by seeking for a relationship (with a person, the ‘object’). This is similar to Bowlby’s theory, in that attachment is primary, but Fairbairn retains a focus on libido (drive and energy) as opposed to Bowlby’s ethological focus on behavioral (proximity-seeking) and cognitive systems (e.g., feelings of security) which become focused around attachment figures.

In Fairbairn’s understanding object relations are the primary explanatory point-of-view:

– Aggression is always a response to frustration of object needs; ‘… aggression is a reaction to frustration or deprivation.‘

-aggression, for these analysts, is not a drive (a form of energy) but an emotional and behavioral response to events.

– hedonism (or masochism or sadism or perversion) results from breakdowns from or traumas which overwhelm normal/healthy/loving object relations.

– Psychopathology is a disturbance in relationships with others. The goal of psychoanalysis is therefore the restoration of direct and full (healthy) relationships with others.

A modern version of object-relations theory within psychoanalysis, dubbed Relational Theory (Mitchell, Wachtel, Bromberg, Stolorow, etc.), which views attachment as primary, and focuses on the experience of self-in-relation-to others, as well as psychological defenses, and relational traumas.

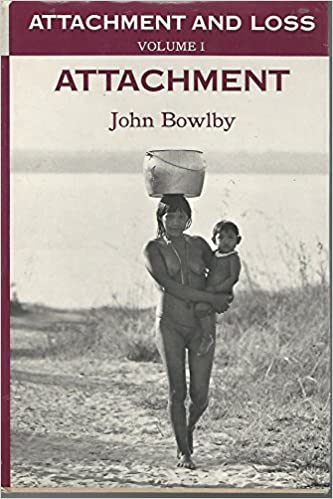

Attachment and Loss

Bowlby’s trilogy, Attachment and Loss, is the seminal work on attachment theory, in which Bowlby proposed an integrated theory of our relationships with attachment figures and the development of these relationships. He explains the person’s responses to separations and losses from attachment figures, as well as the effects of maternal deprivation.

Bowlby also 1) explains the development of Internal Working Models of attachment figures, the cognitive schemas or internal representations upon which later relationships are based, and 2) the effects of attachment traumas (such as separation and loss) on psychopathology (anxiety, depression, pathological grief, etc.). Here are Bowlby’s most important works:

Bowlby’s new metapsychology was based on a specialty within evolutionary biology, Ethology. Bowlby’s key insight (among many) was that our biological need for an unbroken, secure attachment, first to our parents or other attachment figures, and then to others in our lives (people we love) is a basic, evolutionary psychological need.

- For Bowlby the ethological (evolutionary/survival-enhancing) function of attachment is protection: attachment leads to seeking proximity to the attachment figure, which protects (enhances the survival of) the infant and child.

- From a psychological perspective, one of several key functions of attachment is to promote feeling of felt security: the opposite of anxiety.

- Bowlby studied the effects of actual experiences with attachment figures-separations, losses, or deprivations- on attachment security and on emotions and conditions such as anxiety, anger, sadness and depression, normal and pathological grief.

- Bowlby also discussed the origins and treatment of attachment difficulties/disorders.

A key concept of Bowlby was the Internal Working Model, which was an attempt to update the ‘representation,’ and ‘object’ (or ‘internalized object’) concepts of earlier psychodynamic theory. He noted that we form extensive working models of our world, and especially of attachment figures, as we develop.

In current parlance, Internal Working Models are procedural memories, implicit, not necessarily conscious, as opposed to explicit, or declarative memories (such as linguistic, semantic, or autobiographical memories). Implicit or procedural memories govern how we do things, or how we feel. Procedural memories (like walking or riding a bike) do not require a conscious decision to remember. Implicit memory is present at birth. Explicit memories develop later (by age two) and have the internal sensation of “I am remembering” attached to them. These memories include semantic memory, memory for facts, and episodic memory, recalling oneself in a particular situation or moment in time. The storage (encoding) of implicit memories does not require conscious awareness that one is storing information, and the retrieval of implicit memory does not require mental effort or intention to remember. Explicit memory requires conscious awareness of encoding and a subjective awareness of remembering (retrieval).

Bowlby believed (as have all psychodynamic theorists) that the most significant working models are models of the self and of our attachment figures (mother and father). The self is understood/experienced in relation to and in interaction with our attachment figures. From healthy, secure relationships come feelings of security or safety as opposed to anxiety, aloneness, etc.

The sense of the self as competent, worthy, and lovable is based to a very large extent on the relationship history with one’s attachment figures. The ability to be independent, and to explore the world, is connected to the sense of being secure and having attachment figures who are available and supportive.

Bowlby focused on the relationship with the mother. Later students of attachment extended his work to relationship with fathers.

Bowlby believed that internal working models are based on real experiences with attachment figures (as opposed to Freudian fantasies & conflicts between unconscious motivations). He also believed that the negative emotions involved in insecure attachments lead to characteristic psychological defenses such as dismissive exclusion of information and feelings about the attachment figure, or anxious preoccupation with the availability or unavailability of the attachment figure. Defensive exclusion or anxious preoccupation is likely to lead to impaired ability to learn from new experiences, and thus to change or improve one’s sense of safety, competency, and worth.

Bowlby believed that internal working models become more stable over the course of the development, and therefore become persistent, implicit and stable over the course of time, unless some traumatic experience intervenes to disrupt internal working models.

Working models based on experiences during development explain a variety of psychological disorders, including disorders of anxiety, disordered mourning, and depression. They also explain the Freudian phenomenon of transference: in which the patient imposes (projects) his or her (rigid, inaccurate) working models- based on experiences with attachment figures – upon the therapist.

Mary Ainsworth

Mary Ainsworth performed the first study of infant-mother attachment based on Bowlby’s (ethological) Attachment Theory point of view, as described in her book, Infancy in Uganda.

Ainsworth studied 26 mother-infant pairs in Uganda over a nine month period, visiting every-other-week for two hours, documenting the development of the infants’ (1-24 months) proximity-promoting behaviors towards their mothers and the development of preferential behavior by the infants to their mothers.

In particular, she noted the importance of maternal sensitivity to the infants’ signals, emotions and states in the development of the quality of the relationships between the infants and their mothers.

Three patterns of infant-mother attachment were observed by Ainsworth during this study:

- Securely attached infants: they cried little, and were able to explore contently in the presence of their mothers.

- Insecurely attached infants: cried often, even when held by their mothers, and explored little.

- Not-yet attachment infants: who displayed no differential behavior to their mothers.

Infants with sensitive mothers were likely to be securely attached, and babies of less sensitive mothers were more likely to exhibit insecure attachment.

Ainsworth then began the Baltimore project, involving 26 American families, followed from the first month through the first year of life, with 18 home visits over the year, lasting 4 hours per visit. Mothers and their infants were observed in: 1) feeding situations; 2) face to face interactions; 3) situations where the infant cried; 4) infant greeting and following contexts; 5) exploration of the environment (secure base behavior) by the increasingly mobile infants; 6) infant compliance and obedience to maternal directives and prohibitions; 7) close bodily contact between infants and moms; 8) approach behavior; and 8) affectionate contact between infants and mothers.

The Strange Situation and Security of Attachment

The results of the Baltimore project are to be found in a large number of publications and summarized in the book Patterns of Attachment, co-authored by Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters. and Wall.

One of Ainsworth’s core innovations, in addition to her conceptualizations of maternal sensitivity and security of attachment was the Strange Situation, a laboratory technique in which one can observe and classify the infant’s ability to use the mother as a secure base for exploration of the world, under conditions of increasing stress:

In this 22-minute videotaped procedure there are eight brief episodes:

1) Mother and infant are introduced into a laboratory playroom;

2) A novel woman (stranger) comes into the room and interacts with the mother and infant;

3) while the stranger plays with the baby, the mother quietly leaves the room;

4) mother re-enters the room;

5) mother and infant interact in the room;

6) mother leaves the infant alone in the room;

7) the stranger re-enters the room; and

8) mother re-enters the room.

The following videos illustrate the Strange Situation:

Everett Waters Strange Situation Video

Strange Situation Video

Particular focuses of attention in the Strange Situation are: 1) the infant’s ability to explore toys and interact with the stranger in the presence of mom; 2) the infant’s reactions to separation; and

3) the infant’s responses to the mother upon reunion.

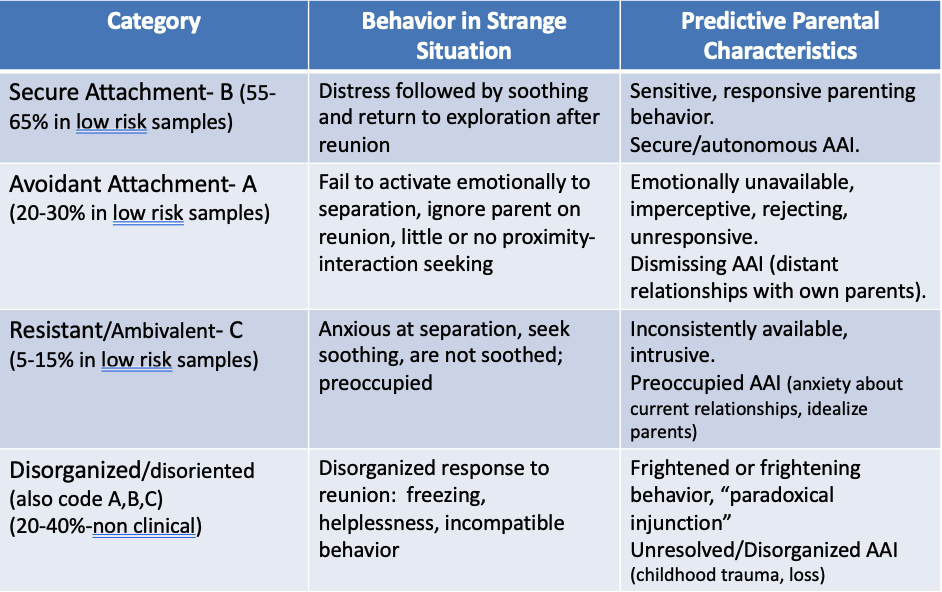

Securely attached children are those who, although distressed by separation, turn to the mother for soothing and comfort upon reunion, seeking closeness, interaction and/or physical contact with her; as opposed to children who exhibit Insecure or Disorganized attachment:

a) anxious and angry (Insecure ambivalent) behavior upon reunion. Infants in the ambivalent insecure group cry and seek contact with mother but do not simply cuddle with mom when picked up by her. They might kick or swipe at her. They are angry and difficult to soothe (5-15% of normal samples).

b) avoidance of the mother on reunion (20-30%). Infants in the Insecure avoidant group seem to “snub” or avoid the mother upon reunion, although they are clearly distressed by the separation (e.g., as measured by heart rate or other physiological measures of distress).

c) disorganized behavior on reunion. he reactions of Disorganized/disoriented children include freezing, turning in circles, approaching and then turning away from the mom, helpless behavior such as emotional or physical collapse, or rocking back and forth; they look frightened, and sometimes trance-like. In normal, non-clinical populations this is present 20-40% of the time.

The majority of children in normal, low-risk samples (like the Baltimore Project) display secure attachment (55-65 percent of children in such samples). Among abused and neglected children the Disorganized attachment pattern is prevalent (as high as 80%). Insecure Organized attachment constitutes 25-45 % in low-risk samples.

Bowlby’s collaborator, Robertson, had filmed the secure and insecure/organized patterns of attachment behavior when children were reunited with their parents after prolonged separations (e.g., after the London ‘Blitz’ during WWII).

The following chart summarizes the work of Ainsworth and her colleagues regarding Security of Attachment: The four groups identified in this research, which has been extensively replicated, are: 1) Securely Attached infants; 2) Insecure/ Resistant-ambivalent Attachment; 3) Insecure/Avoidant Attachment; 4) Disorganized Attachment (identified by Ainsworth’s former student, Mary Main):

Security of Attachment

Children can have distinct attachment strategies for each parent.

In general, children (to varying degrees) use their attachment figure(s) as a secure base from which to explore their surroundings. An enduring pattern of contingent, sensitive responsivity by the mother- who is not burdened by unresolved attachment issues in relation to her own parents- leads to secure attachment.

- The majority of infants (65% in low-risk samples) form secure attachments to their mothers. This is due to sensitive, emotionally attuned respones by their mothers, who lead the infant/child to expect that their mother will be consistently available, and will respond to the infant’s or child’s emotional states in a helpful way (appreciate their positive emotions and soothe and help them regulate their negative states such as anxiety and frustration).

– Sensitive parents have secure children who respond to the strange situation with distress followed by soothing and return to exploration at reunion: secure infants. 55-65% in low-risk non-clinical situations

When there is not a secure internal working model, the parent will not effectively soothe the child, and the child can not use the parent to return to his or her activities

- Avoidant attachments: These children have parents who are emotionally unavailable, imperceptive, rejecting, and unresponsive.

– In the Strange Situation such children act like they ignore parents’ return; they enter a “deactivating” state, minimizing proximity seeking. 20-30% in low risk samples - Ambivalent attachments: parents who are inconsistently available and responsive, intrude their own state of mind on the infant.

– In the SS the children seem anxious, seek soothing, but are not soothed, even angry. They are insecure, preoccupied with the parent, but don’t take comfort. Their response to the strange situation is over-activation of the attachment system. 5-15% of children in low-risk populations

- Disorganized attachments: parents who act frightened, frightening, or disoriented in their communications have children who respond to the return of the parent in a disorganized fashion: walking around in circles, approaching and then avoiding the parent, freezing (looking dissociated or still). (20-40%-non clinical), but may be as high as 80% in maltreated samples.

- One infant hunched her upper body and shoulders at hearing her mother’s call, then broke into extravagant laugh-like screeches with an excited forward movement. Her braying laughter became a cry and distress-face without a new intake of breath as the infant hunched forward. Then suddenly she became silent, blank, and dazed. (Main & Solomon, 1986).

The child may back towards the parent, rather than stand face to face; or may respond to stranger by facing the wall away from m or stranger, then looking back w terror. Dazed behavior and depressed affect are common. Another “fell face-down on the floor in a depressed posture prior to separation, stilling all body movement .

- One infant hunched her upper body and shoulders at hearing her mother’s call, then broke into extravagant laugh-like screeches with an excited forward movement. Her braying laughter became a cry and distress-face without a new intake of breath as the infant hunched forward. Then suddenly she became silent, blank, and dazed. (Main & Solomon, 1986).

- Disorganized attachments show “fear without solution.” Because the infant inevitably seeks the parent when alarmed, parental behavior that alarms an infant should place it in an irresolvable paradox in which it can neither approach, shift its attention, or flee.

Bowlby saw internalized working models, such as these patterns of security/insecurity, not as fixed primitive structures split off from development or from influence by new experiences (the Freudian model), but as cognitive–affective schemas, patterns of emotion, cognition and behavior, which evolve in relation to continuing experiences with attachment figures throughout life. These internal working models organize and underlie patterns of behavior, feeling, and thinking in relation to others throughout life.

Among infants who have been maltreated (abused or neglected) by their parents, disorganized attachment is found in an average of 70 percent of children.

Bowlby viewed internal working models as relatively difficult to change, not because they were based on fantasy and inaccessible to actual experience; rather, but for two key reasons:

- First, internal working models are rooted in the developing person’s efforts to feel safe and in the perceived danger that various kinds of caretaking experiences could create; i.e., some are driven by anxiety.

- Second, few psychological processes are more stable than behavior experienced as an effort to keep one safe (i.e., avoid anxiety).

One way of looking at this is to say that the insecure child is maximizing what is available from the caregiver “under the circumstances”:

- e.g. the ambivalent/preoccupied child extracts caregiving from the inconsistently available caregiver, via intense proximity-seeking towards the caregiver, while the avoidant insecure child avoids rejection by not seeking proximity, or by rejection of the desire for comforting and protection from her caregiver.

- the disorganized child is periodically frightened by the reactions of the attachment figure to her emotions; the caregiver periodically is overwhelmed by the child’s emotional displays (which call to mind unresolved traumas from their own life).

The main source of anxiety, especially in childhood, is fear of losing the attachment figure.

Continuity of Attachment Patterns

Mary Main and Cassidy found a highly significant correlation between attachment behavior at age 1 and patterns of separation-reunion in studies of children with their mothers at 6. They also found that:

- Securely attached infants, as preschoolers, are more cooperative, popular with peers, are more resilient and resourceful, and at age 6, they are more relaxed and friendly.

- Insecure- avoidant infants as preschoolers appear emotionally insulated, hostile, and antisocial; they later tend to distance themselves from their parents.

- Anxious-resistant /preoccupied insecure infants are tense and impulsive as toddlers and passive and helpless in preschool; they later show a mixture of insecurity and hostile behaviorin interaction with their parents.

Elicker et al. (1993) reported that infant attachment style reliably predicts social skill and self-confidence in children 10 years later… secure attachment in infancy predicts more positive relationships with teachers & more socially adept, close friendships with peers.

Hamilton (1994): Among late adolescents who had been assessed as infants in the Strange Situation, there was a 75% correspondence for secure-insecure attachment status between infancy and late adolescence, with the strongest stability in the preoccupied group.

Waters, Merrick, Albersheim, & Treboux followed 50 individuals for 20 years and found 64% stability in attachment classification:

- greater than 70% stability for individuals with no major negative life events

- less than 50% stability for those who lost a parent, endured parental divorce, etc.

A secure base in adolescence was conceptualized by Bowlby as a “goal-corrected partnership,” a freedom to explore thoughts and feelings collaboratively with a parent. Secure-base behavior in adolescence may become most salient during times of stress, negotiation, or conflict.

Disorganized attachment is reflected in: 1) disoriented, odd, out-of-context behavior during parent-child interaction, with 2) poor quality romantic relationships later, and with 3) concurrent depressive & dissociative sx’s.

Attachment, Personality Development, and Psychotherapy

As a result of its stability Insecure & especially disorganized attachments are a significant risk factor for psychopathology.

According to Alan Schore, Daniel Siegel and Peter Fonagy: Attachments are the foundation from which the mind, brain and emotional health develop.

- For Alan Schore, a major contributor to the psychodynamic understanding of attachment, the sensitive (secure) caregiver responds empathically to the child’s affect, engagement, and arousal. Critical to this mother’s (or father’s) management of the child’s emotional state is her ability to coherently understand and respond to the child’s affects and actions. The parent, in effect, uses his or her own mental state to co-regulate the child’s affect (feelings); this in turn contributes the child’s success in learning to regulate his or her own affects.

- Coherently understanding and co-regulating the child’s affective states (both positive and negative emotions) requires 1) empathy (sharing the child’s emotions; 2) effective regulation of one’s own emotions (e.g., not being overly anxious or overwhelmed by the child’s negative affects); and 3) mentalization (the ability to understand mental states- feelings, thoughts, motives, intentions) of the child, and of oneself.

- For Daniel Siegel: The primary feature of secure, healthy attachment is attuned emotional communication between a person (e.g. a child) and an attachment figure.

- Siegel: “…the developing mind uses the states of an attachment figure in order to organize the functioning of its own states… dependent upon parental sensitivity to the child’s signals …and [this] allows the mind of the child both to regulate itself in the moment and to develop regulatory capacities that can be utilized in the future…”

- For Fonagy- a key function of attachment is to teach the child about other minds; i.e., to promote mentalization.

- Bateman and Fonagy: Mentalization is “the mental process by which an individual implicitly and explicitly interprets the actions of himself/herself and others as meaningful on the basis of intentional mental states (personal desires, needs, feelings, beliefs, & reasons).

- ‘Mentalizing’ others is essential for the development of empathy, and reciprocal and healthy relationships with others (e.g., in sensitive and secure parenting).

- Mentalizing the self is essential for self-reflection, self-regulation and identity formation.

The Relationship between a Child’s attachment style and their Parent’s attachment style

Mary Main and Erik Hesse, with their students pioneered the development of the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), a series of questions about their own childhoods, which is used to assess an adult’s “state of mind with respect to attachment.” Solomon and George, students of Main, have developed the Adolescent and Adult Attachment Projective (AAP), a briefer story-telling task, which is strongly correlated with the AAI.

- They have found a strong relationship between attachment as classified with the Strange Situation and the later attachment style of the (now) adult person, as classified with the AAI two decades later. This suggests that adult attachment style and organization is shaped by early experiences with attachment figures.

- Researchers have also shown a strong relationship between a parent’s state of mind with respect to attachment (AAI classification), prior to the birth of their children, and their infant child’s Strange Situation classification with respect to that parent in the Strange Situation at age one.

- The child has a different attachment pattern with each parent, which is strongly correlated with that parent’s attachment pattern (state of mind with respect to attachment).

- These findings strongly indicate that the parent’s state of mind with respect to attachment is a primary determinant of the child’s attachment style.

Attachment Organization and Psychotherapy

Does Attachment organization (or security) affect the process and outcome of treatment?

- Securely attached adult patients are more compliant with treatment. Secure attachment to the therapist predicts a stronger working alliance, more disclosure to therapist & a more intense transference.

- Avoidant/Dismissing patients are less likely to seek help from their therapists, less likely to comply with treatment, less likely to make productive use of treatment

- They are affectively constrained in treatment.

- This is characteristic of all their relationships.

- They are more likely to be diagnosed with drug, alcohol or eating disorders.

- Avoidant/dismissing patients exhibit the least disclosure in treatment.

- They fare best when treatment addresses their avoidance of closeness.

- Preoccupied/anxiously attached patients more likely to self-disclose than avoidant and secure patients.

- They engage with their therapists in more intense and volatile ways;

- Preoccupied patients are more likely diagnesed w mood disorders.

- Higher attachment anxiety (preoccupied) and attachment disorganization predict the least remission in symptoms; success is highest in secure patients.

- Insecure, preoccupied can have a strong attachment, experience intense negative affect and resistance in tx.

- Disorganized patients:

- Disorganized patients are more likely to display severe personality disorders, with more therapeutic ruptures, more shifting alliances and poorer outcomes.

Most therapy patients are insecure, thus interfering with therapeutic effectiveness.

The therapist’s security is also a major factor in the treatment alliance, flexibility, defensiveness, and outcome.

Mentalization and secure attachment are now viewed as essential mechanisms in all effective psychotherapy.

Secure attachment is the acquisition of procedures for the co-regulation of aversive states of arousal, when the child’s affect is accurately but not overwhelmingly experienced, reflected back and responded to empathically by the attachment figure or therapist.

During development:

- A dismissing parent may fail to mirror the child’s distress; as a result the child shuns the affective state of the caregiver.

- A preoccupied parent may represent the child’s distress with anxiety; the child focuses on her own state of distress rather than the caregiver’s.

- A disorganized parent may panic, regress, dissociate. It is not safe for this child to think about the internal state of the parent; they are hyper-vigilant to the parent’s mental state, but their own state is dysregulated and incoherent, like the parent’s.

- What is critical is not only that the parent mentalizes the child, but developmentally 1) that the child learns to mentalize herself, on the basis of the parent’s empathic and accurate mirroring, and 2) the child learns to mentalize others’ mental states.

During therapy:

- A therapist needs to mentalize a patient, empathize with the patient, provide security so that the patient can safely experience and express their feelings, and help the patient to can help the patient to co-regulate their aversive states of arousal, and experience the positive feelings which arise in response to transformative change (growth).

- What is critical is not only that the therapist mentalizes the patient, but developmentally:

1) that the patient learns to mentalize him/herself, on the basis of the therapist’s empathic and accurate mirroring, and 2) that the patient learns to regulate their aversive emotions, based on the therapist’s co-regulation of their emotions.

How are Disorganized patients (15% in the population) Different from a clinical perspective?

Main and Hesse described the disorganized attachment phenomenon as: “Fright without solution.”

- As noted on the AAI, disorganized/unresolved AAI patients show disorganization and disorientation (falling silent, lapses in the monitoring of discourse) during discussions of potentially traumatic events (e.g., deaths, abuse).

- These suggest overwhelming feelings &/or dissociative processes.

Mothers’ disrupted affective communication (negative intrusive behavior, role confusion, disorientation, contradictory or unresponsive communication, frightened withdrawal, threatening) and the child’s Disorganized classifications in infancy have been strongly related to dissociative symptoms in adulthood. This connection is stronger than the known connection between abuse and dissociative symptoms.

The following problems/risks are also associated with Disorganized Attachment and maternal disrupted communication (frightened or frightening behavior, withdrawal from or avoidance of the chid): Borderline Personality Disorder, Substance Abuse, Depression.

For disorganized patients, who often have experienced traumas, the resolution in treatment of discrete traumatic events is likely to occur more easily than resolution of role-reversal, disorientation, and disrupted affective communication in the therapeutic relationships.

Can Psychotherapy Change Attachment Orientations?

The evidence is still limited:

- Fonagy et al studied non-psychotic inpatients via AAI on admission and discharge: All patients were insecure on admission, 40% secure on discharge.

- Levy and colleagues, performed a Randomized Control Trial with the AAI and Transference Focused Psychotherapy (Kernberg) . They observed a significant increase in Security. Another study from the same group failed to replicate the finding.

- Stovall-McCullough & Cloitre: Studied women w PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). At the onset of treatment, 72% were ‘D,’ 11% were secure. At end of treatment, 50% were secure.

In the anecdotal treatment literature, examples abound of decreased anxiety, avoidance, and increased organization; but these changes appear, at present, to resist measurement.