A therapeutic assessment of a 6-year-old dysregulated boy.

Therapeutic Assessments with Children and Adolescents are Systemic interventions, in which psychological assessment is used to help parents and important others (e.g., teachers, therapists) gain a more accurate, coherent, compassionate and useful understanding of a child or adolescent.

An additional goal of these interventions is to help parents, teachers, etc. to understand how they contribute to a child’s difficulties and/or can best help him or her.

With adolescents and some older children, the goal includes helping the individual to experience some insight into the meanings of their behavior, and to have someone empathize with their core affects and anxieties.

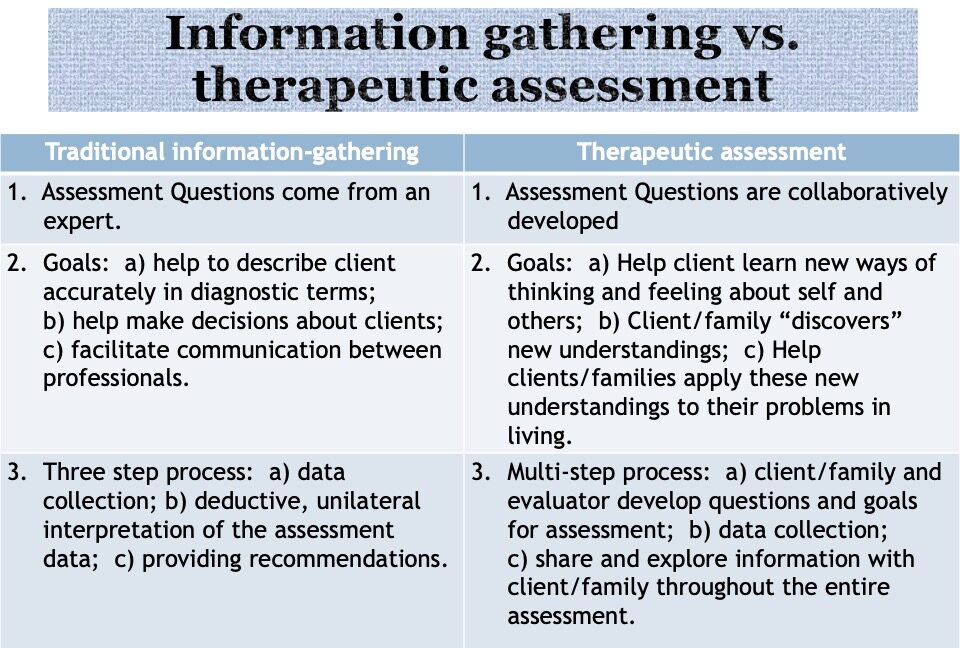

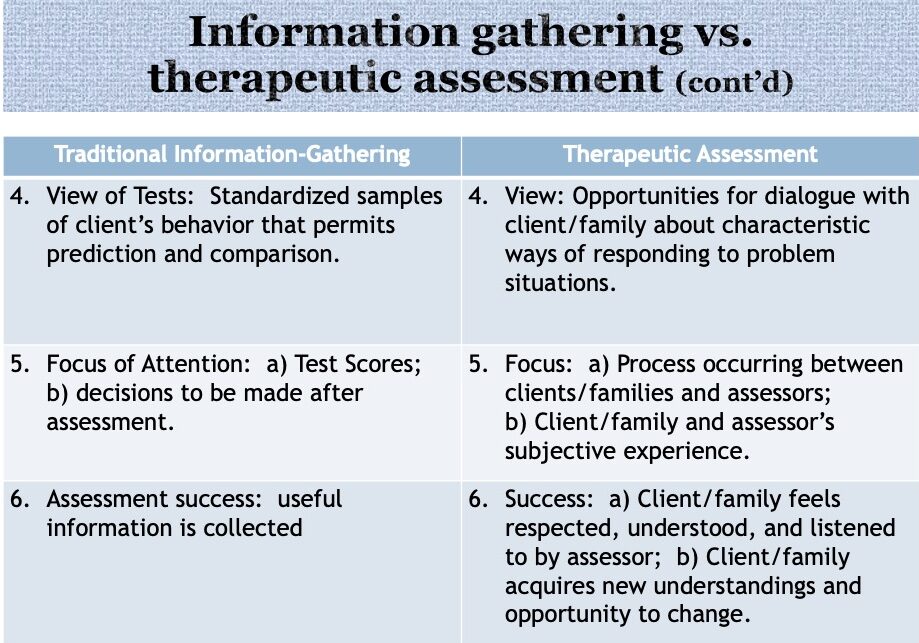

Information gathering vs. therapeutic assessment

Traditional psychological assessment can be described as an information-gathering, as opposed to a therapeutic enterprise (Finn and Tonsager, 1997):

Therapeutic Assessment was developed by Stephen Finn, Ph.D., with important contributions by Constance Fisher and Leonard Handler. (Here is link to a bibliography for Therapeutic Assessment)

In Traditional Assessment:

1. Assessment Questions come from an expert (a psychiatrist or therapist)

2. The Goals are: a) help to describe client accurately in diagnostic terms; b) help make decisions about clients; and c) facilitate communication between professionals.

3. Assessment is a 3-Step process: a) data collection; b) deductive, unilateral interpretation of the assessment data; and c) providing recommendations to the referral source.

Very little information is shared with the assessment client, and interpretations of test data are unilateral in that the client does not participate in constructing them. Very little information is shared by assessors with clients, until verbal feedback sessions or written reports are created.

In Therapeutic Assessment:

1. Assessment Questions are generated by the client (and a referral source, such as a therapist if applicable); with a child we’re talking about the parents (with a teen its both client and parents):

In a first session, even before history taking, the collaborative process is explained to the patient, and the evaluator wants to know what questions the assessment can answer for the client. The therapist helps patient to clarify, refine, even generate questions based on history and current functioning. The evaluator’s primary task throughout is to be sensitive, attentive, and responsive to the patient’s needs and to foster opportunities for self-discovery and growth throughout the assessment process.

2. The goals in TA are not merely to diagnose, or describe, or for professionals to make decisions; rather, the goals are therapeutic, ie, to foster change. We are not asking, ‘is this child bipolar, ASD, ADHD, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder?’ These terms are effective for decision-making or determining eligibility for medical or educational services.

In contrast, In TA the major goal is for clients and families to leave their assessments having had new experiences, gained new information about themselves that help them make changes in their lives. Even a child can develop insight, acceptance, and improved self-regulatory skills if the assessment is done effectively, if the assessor is sensitive, empathic, attentive, and responsive to their needs to foster self-discovery and growth.

3. While therapeutic assessors use similar assessment instruments (tests), clients and families are seen as essential collaborators and are invited to actively assist in numerous aspects of their assessments. For example, clients and families are typically asked to comment on the accuracy of possible test interpretations, and often, in my experience, enrich, broaden and deepen the understandings which stem from test results themselves.

4. In the traditional information-gathering model of assessment, psychological instruments are methods which provide the assessor with standardized samples of clients’ behaviors. Thus, tests permit statistical comparisons with the norm and predictions of the client’s behaviors outside the assessment setting. A test is highly valued if it can be shown to demonstrate adequate reliability, stability, and validity, and in particular, predictive utility.

Although the therapeutic model of assessment considers the statistical properties of psychological tests to be very important, it also views tests as: 1) opportunities for dialogue between assessors and clients about clients’ characteristic ways of responding to usual problem situations, and 2) as tools for enhancing assessors’ empathy about clients’ subjective experiences. As a result, test scores are often analyzed from an idiographic (individualized, personal) as well as nomothetic (statistical) perspective. Thus the goal is to understand the person, not just to generate test scores.

5. In the information-gathering model, the focus of the assessment is on the test scores, and on decisions to be made after the testing is done (e.g., generating an, IQ, diagnosing a learning disorder, prescribing medication for anxiety or depression).

The goals of therapeutic assessment are interventional, that is, it is intended to promote change. As a result, a focus is on the client and family’s subjective experience Assessors are participant-observers who play an active role, along with the client, in shaping the assessment process. The assessor’s interpersonal skill (e.g., his or her empathy, ability to step inside the patient’s shoes, ability to explain in an understanding way), his or her competence as a therapist, and his or her human presence, are the focus of experience and key to success.

A successful assessment, in a TA context, is not just the collection of information which is useful for a diagnosis or decision-making, although this is always the case, but also a relational experience in which the client and family feel respected, engaged, appreciated and understood; an intervention in which the client and/or family learn new ways of being in response to the assessment; and an intrapsychic experience in which the client feels understood, more capable, and less demoralized or abused after the assessment.

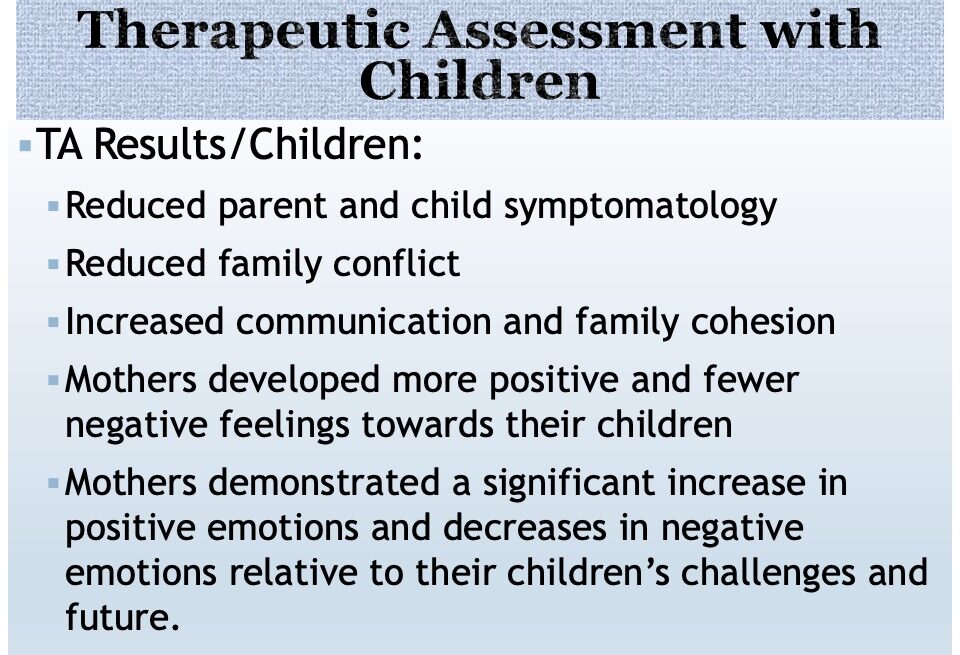

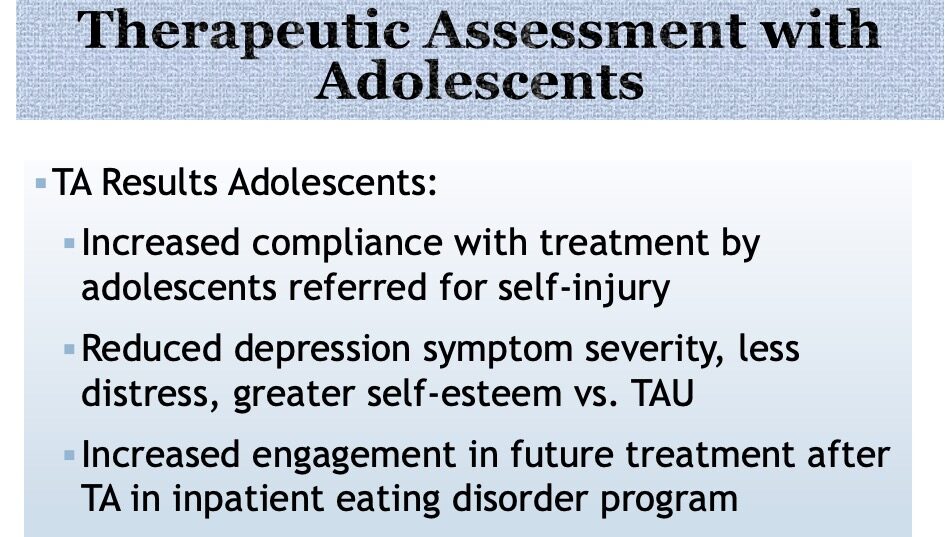

Research on therapeutic Assessment (TA) with children and adolescents demonstrates the following beneficial effects:

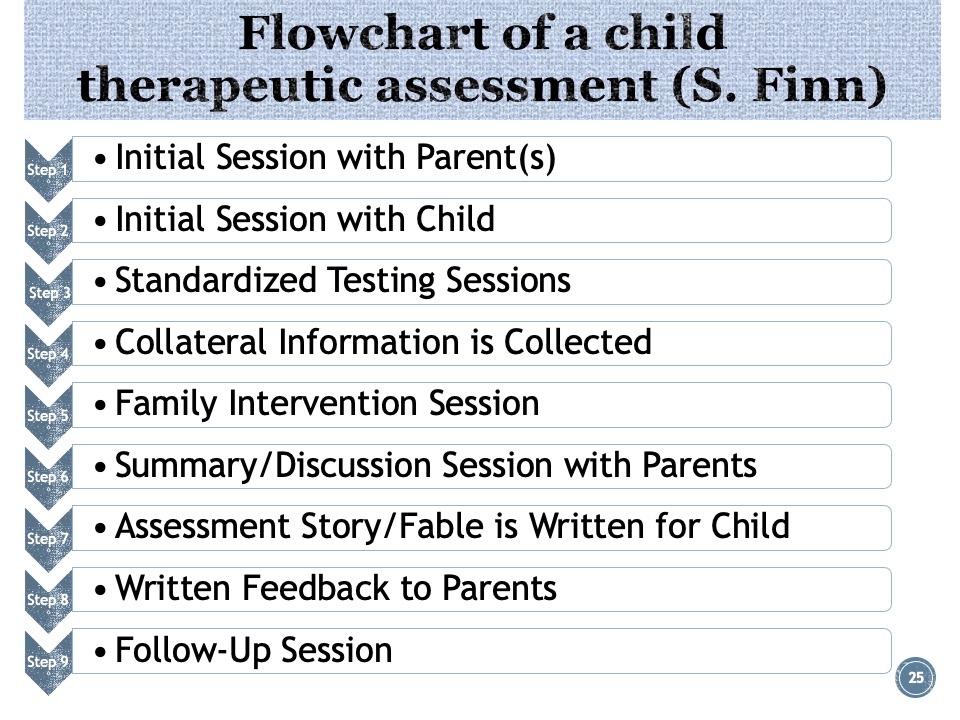

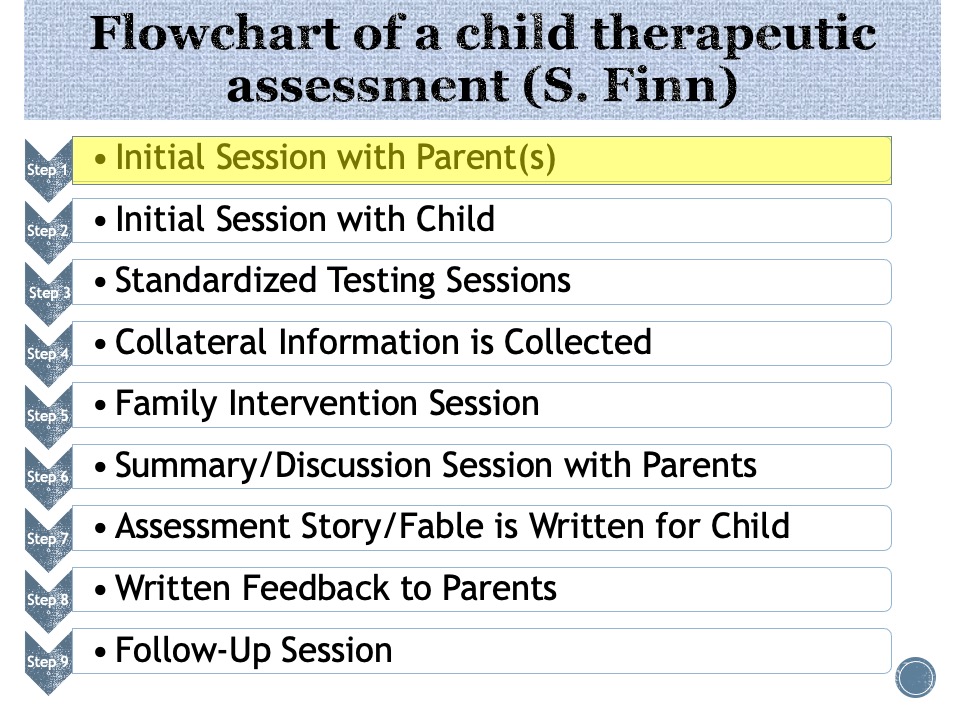

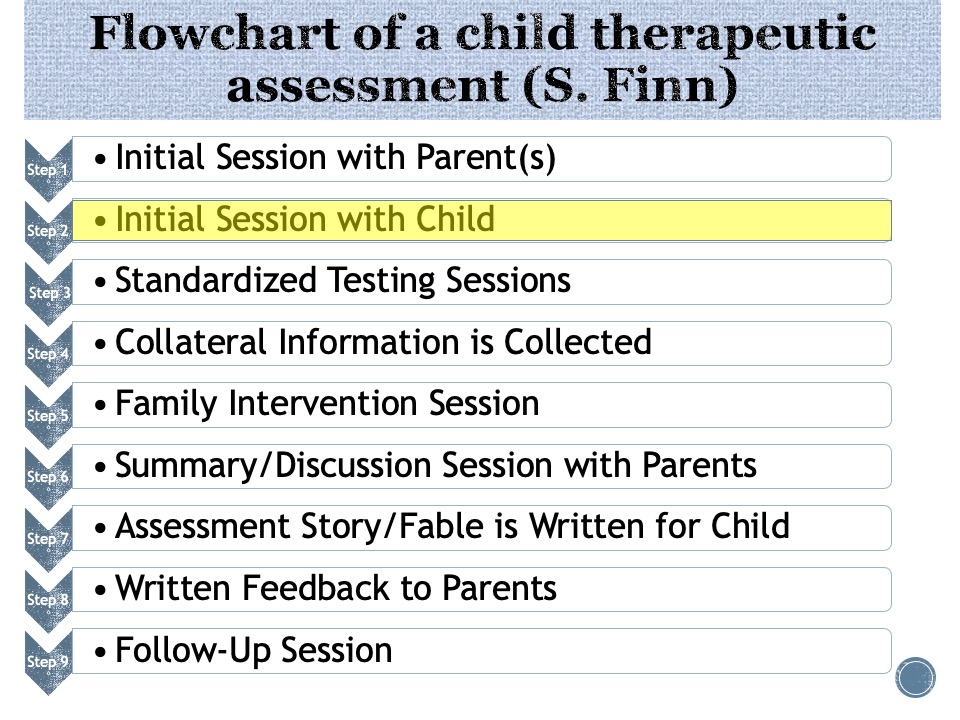

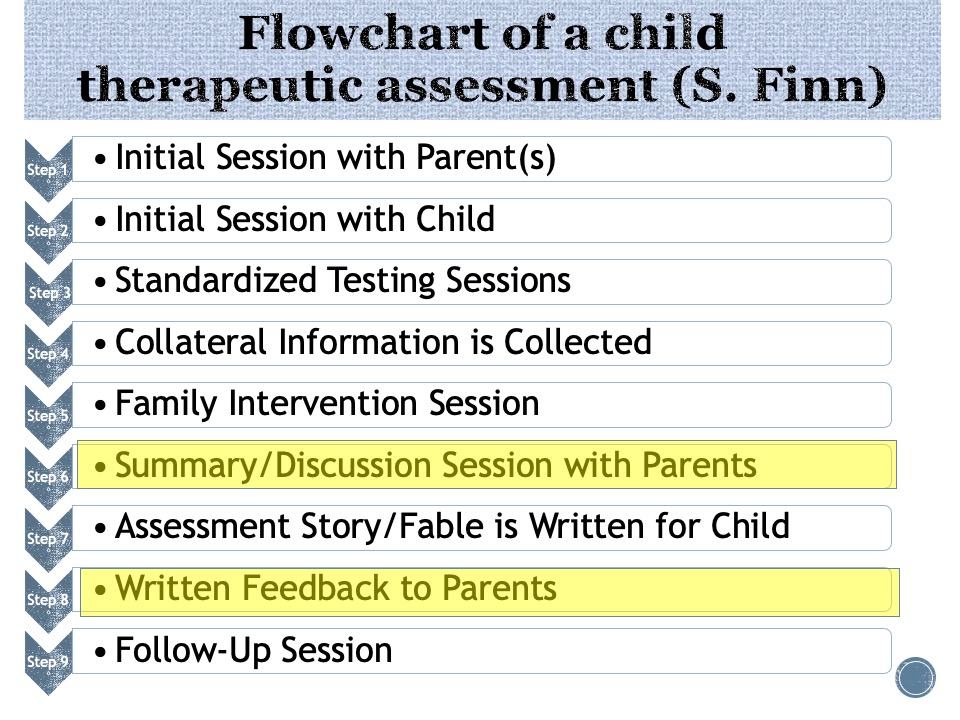

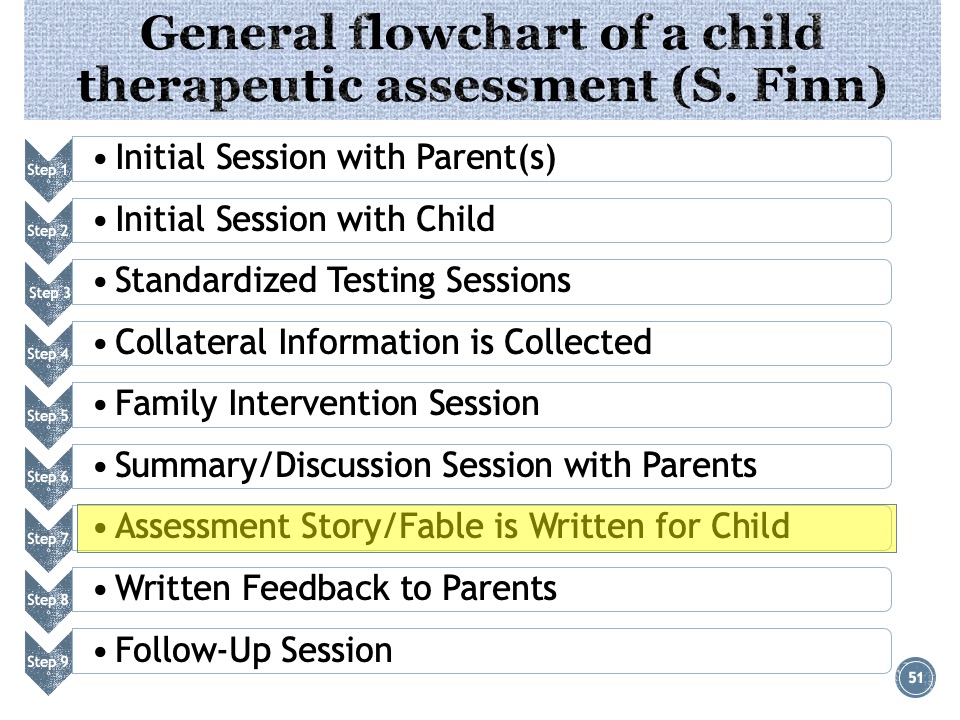

Here are the steps of a therapeutic assessment:

1• Initial session: the parents and psychologist discuss assessment goals. The assessor reveals the questions the referring professional hopes will be addressed, assessor and family work together to define the questions the family and patient hope to be answered by the assessment. The assumption is that answers to the client or family’s questions are more likely to have a therapeutic impact than someone else’s questions.

•As opposed to a standardized and broad-spectrum symptom and history collection, the assessor collects background information relevant to each question. My experience is that essential information is not missed in this process. This gives the parents the opportunity to be listened to, and often leads to insights, in addition to a therapeutic connection with the assessor.•Step 1: yields assessment questions.

Step 2 is essentially the same as in any initial session with a child, except, if the child is old enough, he or she will be invited to pose questions. Tests are selected to assess the individual’s questions, as well as the family (and therapist, if applicable)

Step 3: Is similar to traditional assessment, in which psychological tests are administered in their standardized fashion. This could include (if appropriate to the questions developed in Steps 1 and 2): 1) cognitive tests, including IQ, achievement, neuropsychological, memory, attention and executive function assessments; 2) emotional and personality tests, including self-report tests

•Due to time and space, I’m not going to discuss the family intervention session for this case: this often involves a family task, sometimes a conjoint Rorschach or story-telling task, in which the family is encouraged to discover and try on changes to dysfunctional patterns of interaction, like coercive cycles, escalations, rescues, etc.

•Summary and Discussion are usually 2-4 weeks after onset of the assessment. Not only do the parents a referring professionals get a report, but in many cases the child also receives written feedback in the form of a fable.

A CASE EXAMPLE- CHRIS

So now let’s look at Chris, a 6-year-old child referred by a therapist for a therapeutic assessment:

In this case the initial session is with the parents, which will be followed by a meeting with the child, Chris.

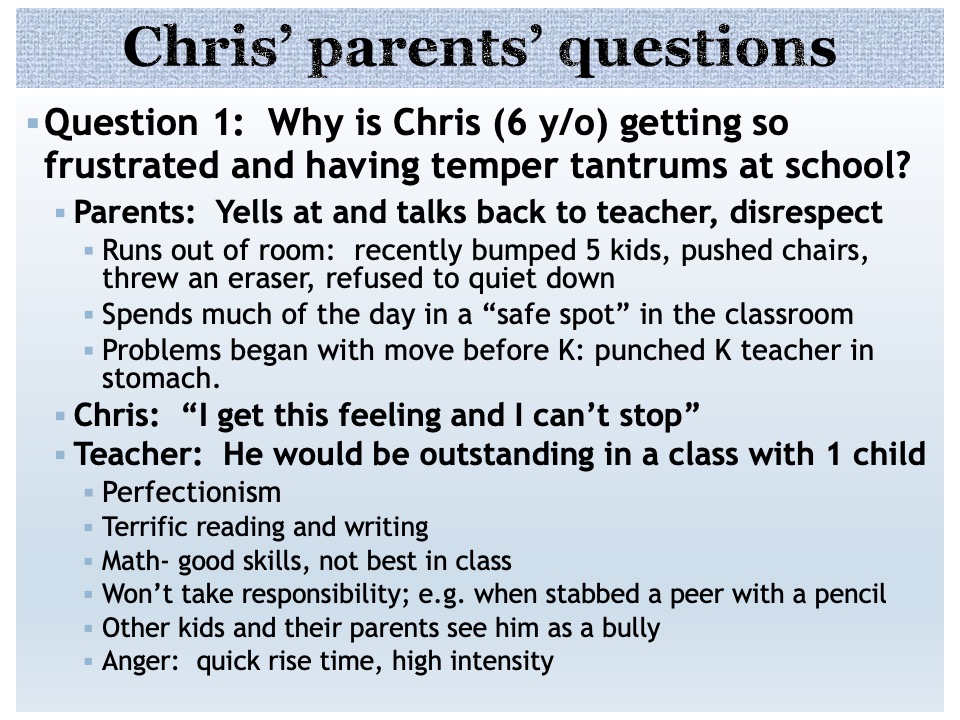

Chris, age 6, was referred to determine the best way to address aggressive behavior and tantrums in class. Chris spends much of the day in a “Safe Spot” in the classroom.

Question 1: Why is Chris getting so frustrated and having temper tantrums at school?

- He yells at and talks back to the teacher (1st grade). He shows disrespect, runs out of room. He recently bumped 5 kids, pushed chairs, threw an eraser, and refused to quiet down

- Problems began with the family’s move before Kindergarten: Last year he punched the teacher in the stomach. There were no problems noted in preschool- he was a rule abider.

- There are also no behavior problems at home. He said to his mother: “If you were there, I’d be good!” He Is good to his younger brother. He was never hyperactive, and sleeps well. He “used to talk back to us more… not any more. “When he talks back to us. We’re calm, can talk him down.”

- “Both of us have tempers. We yell; nothing explosive; we’re working to tone it down. It doesn’t work with Chris.”

- He won’t take responsibility for his behavior; e.g., when he stabbed a peer with a pencil

- Other kids and their parents see him as a bully.

- His anger is quick to rise, and comes only in high intensity.

Chris says in his initial one-on-one session: “I get this feeling and I can’t stop”

His teacher says: He would be outstanding in a class with 1 child. He is terrific at reading and writing. His math skills are good, though not the best in the class.

Chris can’t let anyone else do well: he puts them down, says something mean. This appears to be related to a pattern of Perfectionism: He is very hard on himself, if he doesn’t finish work first in the class, if he is not the best (esp. in math), Chris lashes out verbally and/or physically. He spent 2 weeks on one drawing because of worries about errors.

He wants to be friends, but other kids are annoyed by him.

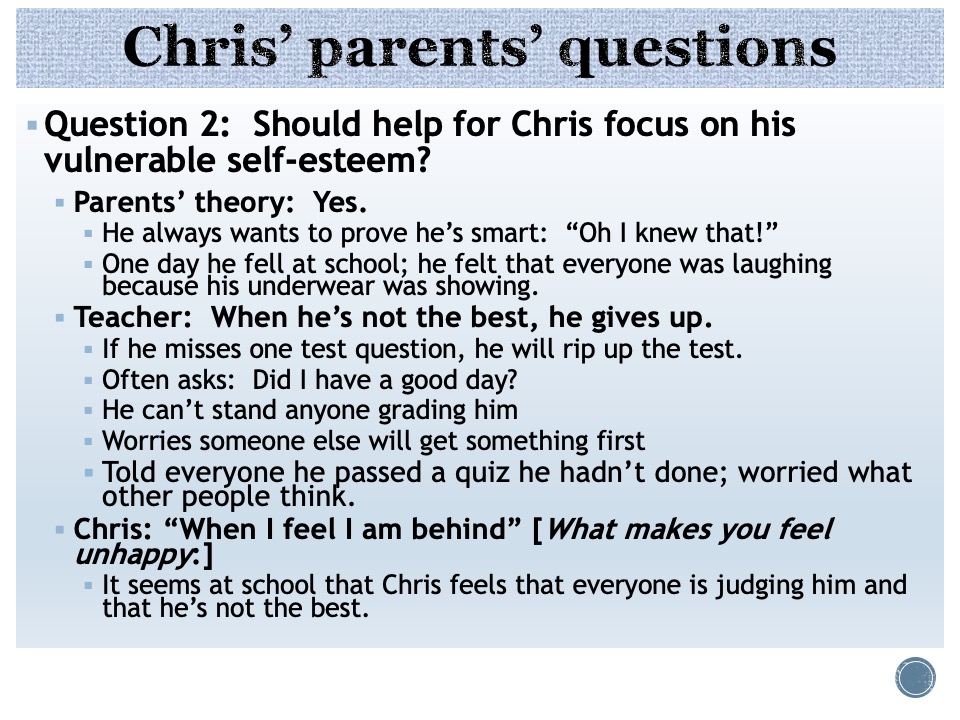

Question 2: Should help for Chris focus on his vulnerable self-esteem?

- Parents’ theory: Yes. Chris always wants to prove he’s smart: He often says: “Oh I knew that!”

- One day he fell at school; he felt that everyone was laughing because his underwear was showing.

- Teacher: When he’s not the best, he gives up. If he misses one test question, he will rip up the test.

- He often asks: Did I have a good day?

- Chris told everyone he passed a quiz he hadn’t done; seems very worried what other people think.

- In his interview: I asked Chris What makes you feel unhappy: “When I feel I am behind” “One time I accidentally did something wrong”

- He says: “I used to have a problem with my temper…”

- It seems at school that he feels that everyone is judging him and that he’s not the best.

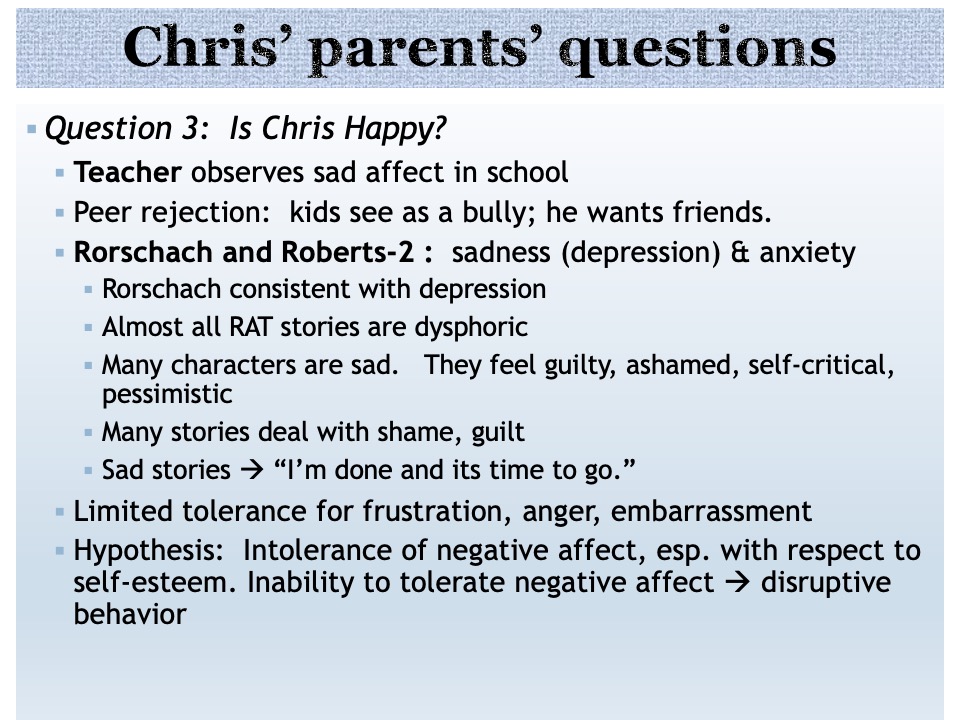

Question 3: Is Chris Happy?

- His parents describe him as “brooding.”

- His Father says: “A switch gets flipped and he’s disruptive…”

- His Mother says: “He’s very sensitive”

- His Teacher reports: “He seems very anxious… He gives up, can’t get unstuck, worries about how he’s doing… He seems sad (face and body language), with fragile self-esteem…”

- Chris aways says “I’m the best”

- Chris: I “used to” have a problem with my temper

- Both parents have a history of anxiety disorder

- Mom treated in past with SSRI. Dad is also currently also on an SSRI.

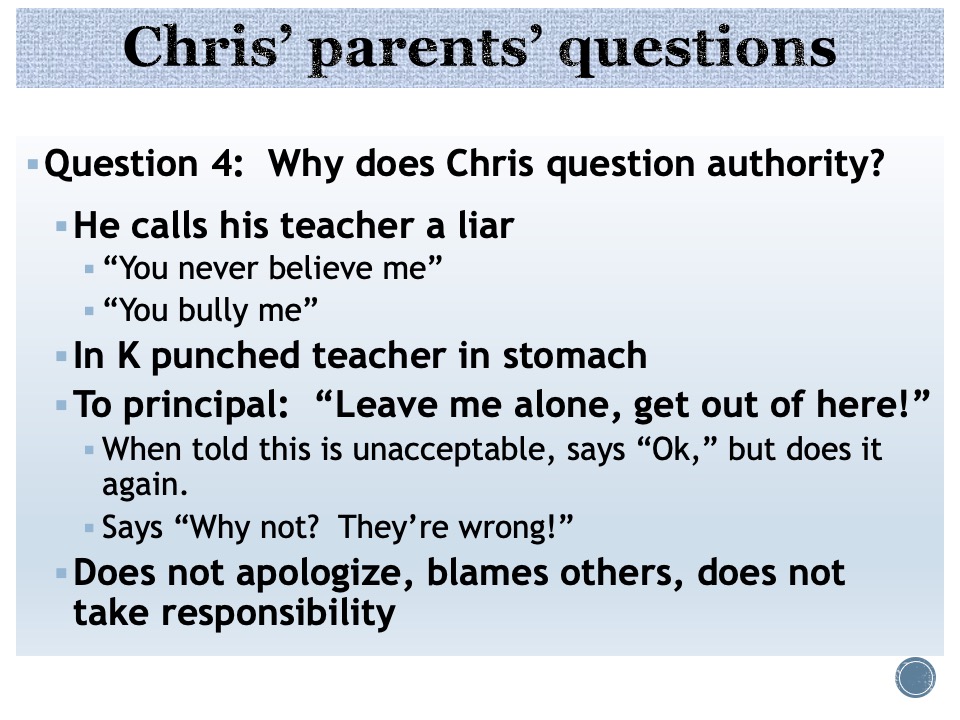

Question 4: Why does Chris question authority?

- He calls his teacher a liar He says: “You never believe me,” “You bully me”

- In Kindergarten he punched his teacher in stomach

- To his principal, he said: “Leave me alone, get out of here!”. When told this is unacceptable, he says “Ok,” but does it again.

- When confronted by parents with his verbal and physical aggression or defiance at school, Chris says “Why not? They’re wrong!”

- Overall, Chris does not apologize, blames others, and does not take responsibility for his actions or misdeeds.

Chris told me in our first meeting that he used to have problems with temper tantrums, but not anymore. Chris tells me he doesn’t need to be here: “I used to get real real grumpy, a long time ago,” he tells me “My teacher had to shut it down” “Its better now…” he says; (Not true)

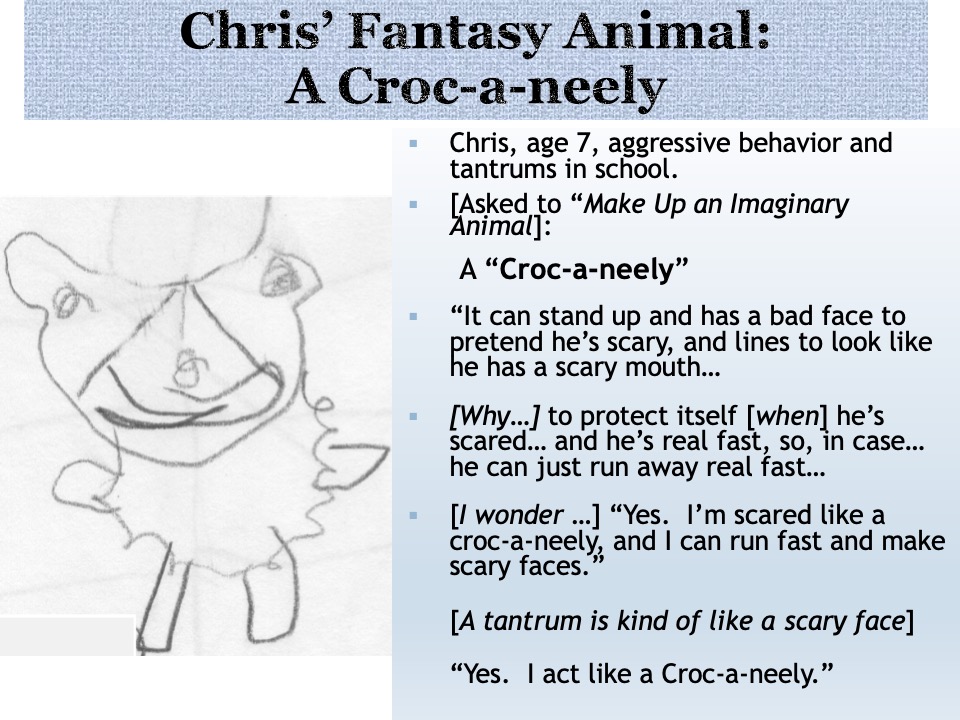

Asked “Draw a Make-Believe Animal, that no one has seen or heard of before” (Handler, 2012): Chris drew what he named a “Croc-a-neely: “

“It can stand up and has a bad face to pretend he’s scary, and lines to look like he has a scary mouth…”

‘Why does he want to pretend he’s scary?,’ I asked Chris:

“To protect itself [when …] he’s scared… and he’s real fast, so, in case… he can just run away real fast

‘What do you think he’s feeling in the picture? “He wants to be alone. I like to be alone. He doesn’t want anyone close to him… “

‘I wonder if you sometimes feel scared like you need to act like a croc-a-neely?’ “Yes. I’m scared like a croc-a-neely, and I can run fast and make scary faces …”

‘A tantrum is kind of like a scary face’ “Yes. I act like a croc-a-neely.”

This led to a discussion of his Chris’ feelings, what makes him feel happy, unhappy, etc.

-Note that the crocaneely is an embodied metaphor, closely associated with an feeling, a facial expression, and an avoidant stance towards attachment (ie, ‘I want to be alone’). Bodily sensations, emotions, facial expressions, and implicit relational knowing are all right hemisphere phenomena (Schore). The “Story” of the drawing allows these implicit or unconscious elements to be reflected upon together by the evaluator and Chris.

In other words, I noted that with the attunement established by inquiring into this metaphor, Chris could display a surprising capacity for self-reflection; this is a positive sign for treatment.

The following procedures were used to assess Chris:

The following were observations of Chris’ behavior during the administration of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fifth Edition (WISC-V). The initials (e.g., BD, LN, VP) represent subtests of the WISC:

- Anxiety/Insecurity/ Perfectionism

- Disinhibition

- Persistence

Here are some more behavioral observations from the WISC-V. Note that this test is not just used as a way of obtaining scores, like IQ, but rather as a standardized situation for observing the child:

- Limited frustration tolerance

- Defiance

- Defensiveness

- Irritability

- Counter-dependence

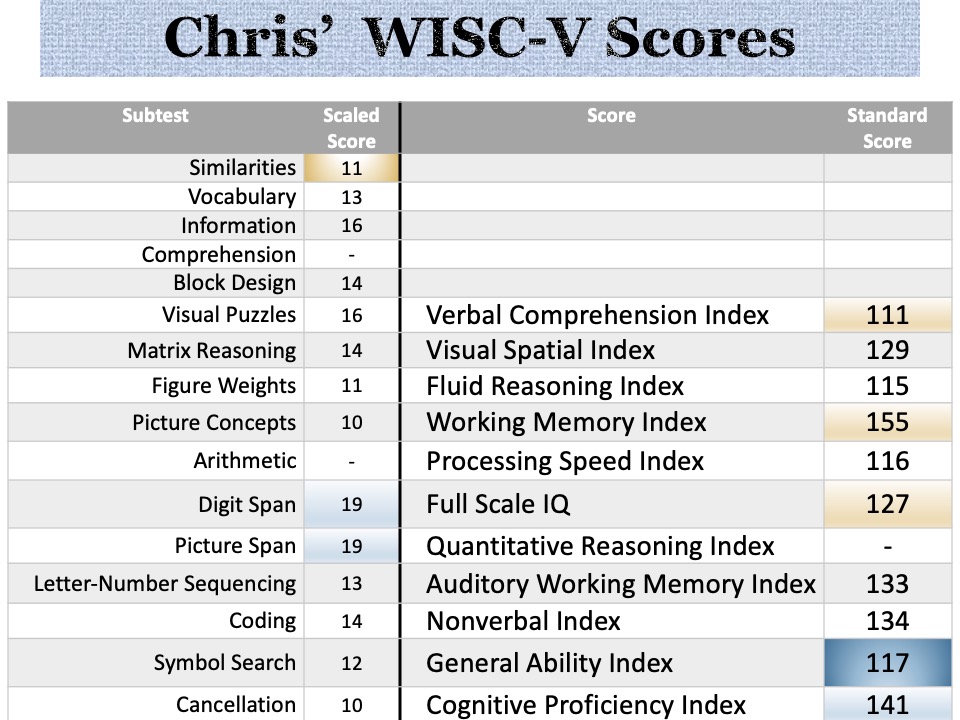

So what do we see here? (for psychologists):

- A 44 point spread between lowest (VCI) and highest (WMI) composite score

- GAI of 117 is a better predictor of academic achievement than FSIQ 127, because

- There is a significant and unusual difference between the WMI and FSIQ, and between WMI and VCI

- Incredible working memory; superior to every other composite score that contributes to IQ

- Visual Spatial ability superior to VC, WM and FR

- No composite score was Average or less; and no subtest score was below the mean

- CPI > >GAI (24 points)

- Nonverbal > VCI

- According to his parents and teacher, Chris is above-average in all academic subjects; so despite all this unevenness, he does not appear a candidate for SLD eval.

- Parent and teacher questionnaires, while indicative of aggressiveness and impulsiveness in school, defiance at school but not at home, are not consistent with hyperactivity or attention problems.

- Social difficulties at school were indicated; specifically peer rejection and conflict with others.

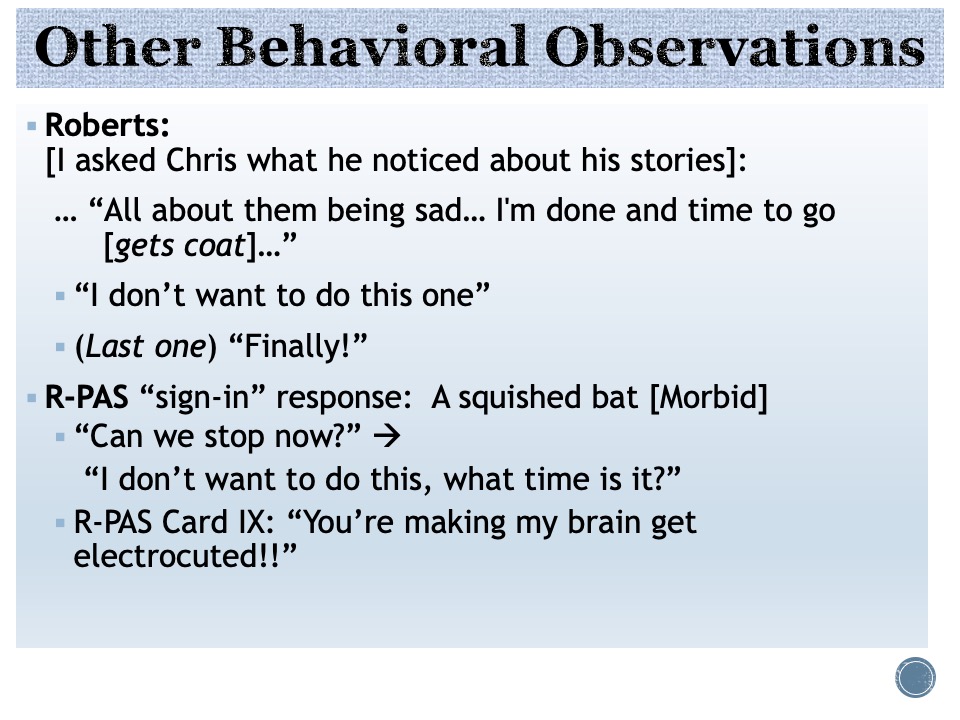

Roberts: [I asked Chris what he noticed about his stories: 1) A boy “sad at himself” because he pushed somebody and they got hurt”; 2) A mom and dad hugging because they are “sad… and they are crying together”; 3) a boy “thinking about his dead dog]

… “All about them being sad” [have anything to do with U] “yeah my fish died … my mom and dad hugged each other when my grandpa died. I’m done and time to go [gets coat]” (THIS IS CONSISTENT WITH OBSERVATIONS FROM THE WISC-V:) Anxiety, or other affect –> defiance, acting out, anger:

- “I don’t want to do this one” (last) “Finally!

It also suggests depressive affects, which is consistent with his Rorschach:

R-PAS “sign-in” (first) response: A squished bat [Morbid]

- “ Can we stop now?”

- “I don’t want to do this, what time is it?”

Again, CONSISTENT WITH OBSERVATIONS FROM THE WISC-V: So now, we’re going to look for other evidence to confirm or refute the hypothesis that affective dysregulation –> acting out, anger, defiance, aggression - R-PAS Card IX: “You’re making my brain get electrocuted!!”

- After R-PAS: “I hated it”

What I’m going to do next is to talk about test results in the context of answering the assessment questions. I will focus on how these observations from the WISC-V and the results of other tests integrate into a picture of Chris which answer the parents’ questions

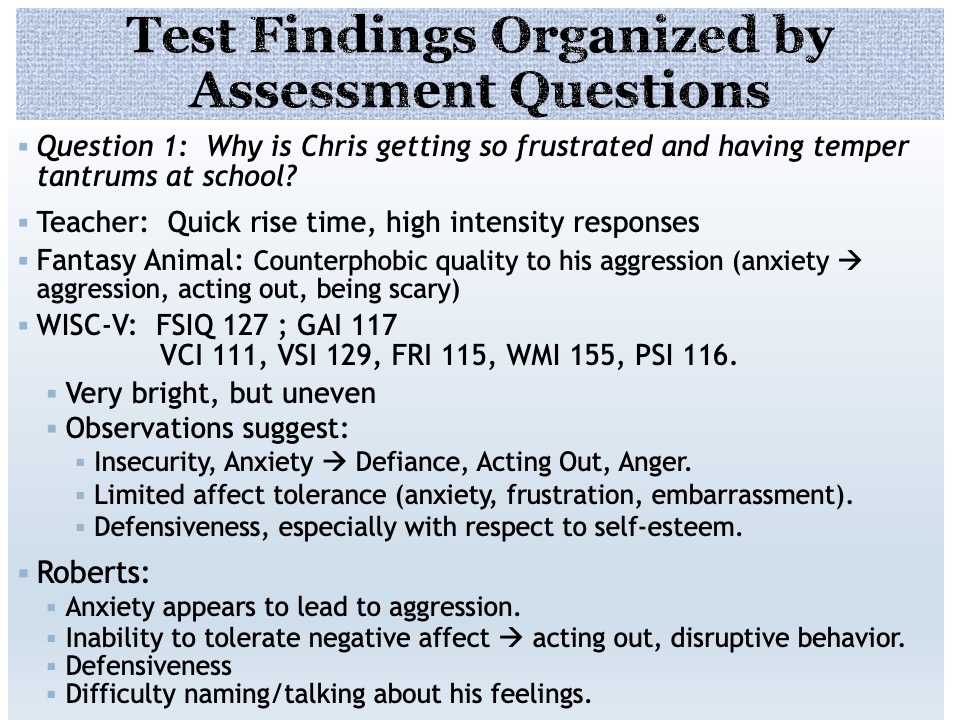

- Question 1: Why is Chris getting so frustrated and having temper tantrums at school?

Teacher: Quick rise time, high intensity responses: speaks to temperament, affective regulation difficulties

Fantasy Animal (Croc-a-neely) Counterphobic quality to his aggression (anxiety –> aggression, acting out, being scary) - WISC-V: FSIQ 127 GAI 117

VCI 111, VSI 129, FRI 115, WMI 155, PSI 116.

Very bright, but uneven - Insecurity, Anxiety –> Defiance, Acting Out, Anger

- Limited affect tolerance (anxiety, frustration, embarrassment)

- Defensiveness , especially with respect to self-esteem

- Roberts:

Confirms hypothesis that Anxiety leads to aggression.

Inability to tolerate negative affect à disruptive behavior.

Difficulty naming/talking about his feelings.

E.g., One story: people are crying (Next) “That I rule the world!”

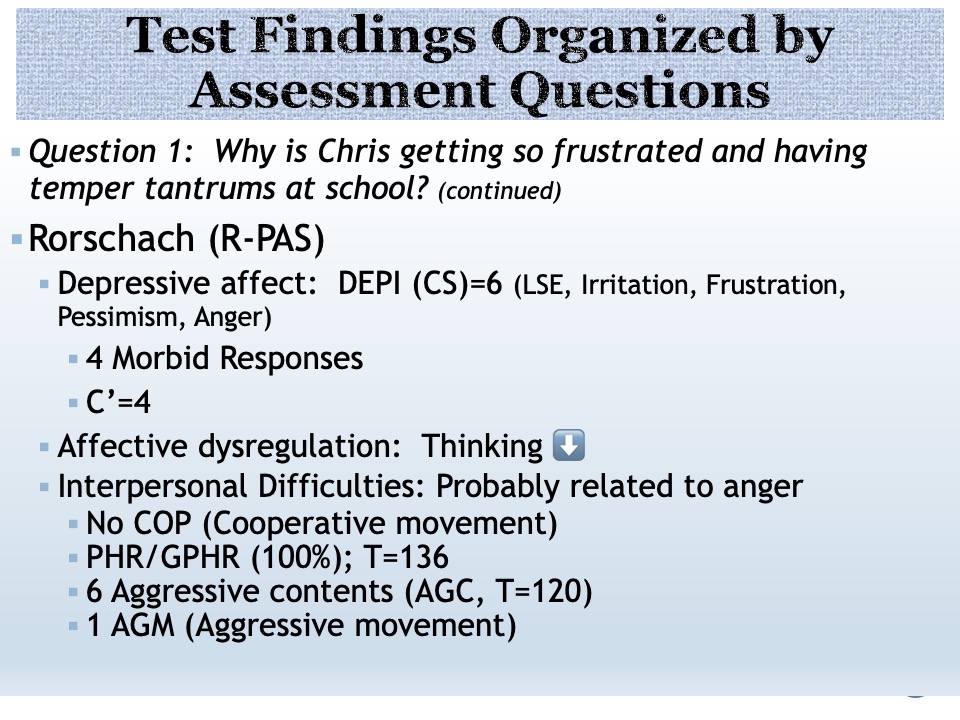

Question 1: Why is Chris getting so frustrated and having temper tantrums at school?

- The Rorschach is consistent with these hypotheses:

(Insecurity, Anxiety –> Defiance, Acting Out, Anger)

(Limited affect tolerance (e.g.,, for anxiety, frustration, embarrassment)

(Defensiveness , especially with respect to self-esteem)

And also suggests the following: - Depressive affect: Old DEPI (CS, not RPAS) DEPI=6 (LSE, Irritation, Frustration, Morbidity, Anger)

- MOR=4 (T=123) Squished bat, turkey with a hole in it, a bird with holes in its wings

- Consistent with fragile self-esteem

- C’=4 (T=117): irritation, negative feelings coming from both inside and outside sources

- I also found evidence that Emot. intensity–> flooding & Cognitive dysregulation

- In other words Affective Dysregulation –> Thinking ⬇ FQ decreases with color cards; some Level 2 special scores there.

- As his dad said, a “Switch is flipped”: Emotional dysregulation –> Cognitive dysregulation

- Interpersonal Difficulties: Probably related to anger

- No COP (cooperative movement)

- PHR/GPHR (100%); T=136 Implies difficulty/ineffectiveness in relationships

- 6 Aggressive contents (T=120) e.g., sharp teeth, claws, samurai, an evil rabbit

- 1 AGM:: An angry spider

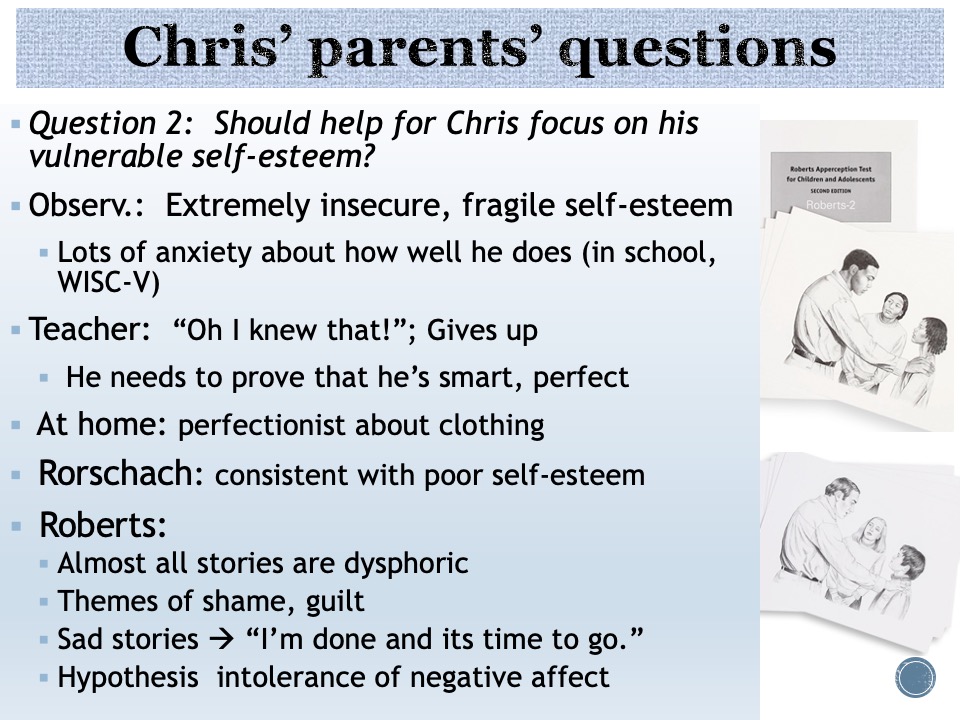

Question 2: Should help for Chris focus on his vulnerable self-esteem?

- Extremely insecure, fragile self-esteem:

- Observed lots of anxiety about how well he does (in school, per teacher report, and all over his behavior during the administration of the WISC-V)

- Teacher: “Oh I knew that!”, gives up

- He needs to prove that he’s smart, perfect; rips up test if he gets one wrong

- Math: if he cant get to choice time by finishing his work ahead of everyone else -> angry, bad behavior

- Is he aggressive to teacher, peers to deal with sadness, embarrassment?

- Why does he seem so vulnerable to shame?

- It seems that at school he feels that everyone is judging him; that he needs to be the best and finds it intolerable when he’s not the best

- Roberts:

- Almost all stories are dysphoric;

- Many characters are sad. They feel guilty, ashamed, self-critical, pessimistic

- Many stories deal with shame, guilt

- Sad stories–> “I’m done and its time to go.”

- Hyp. intolerance of sad affect, esp. with respect to self-esteem.

- One story: people are crying (next) “That I rule the world!”

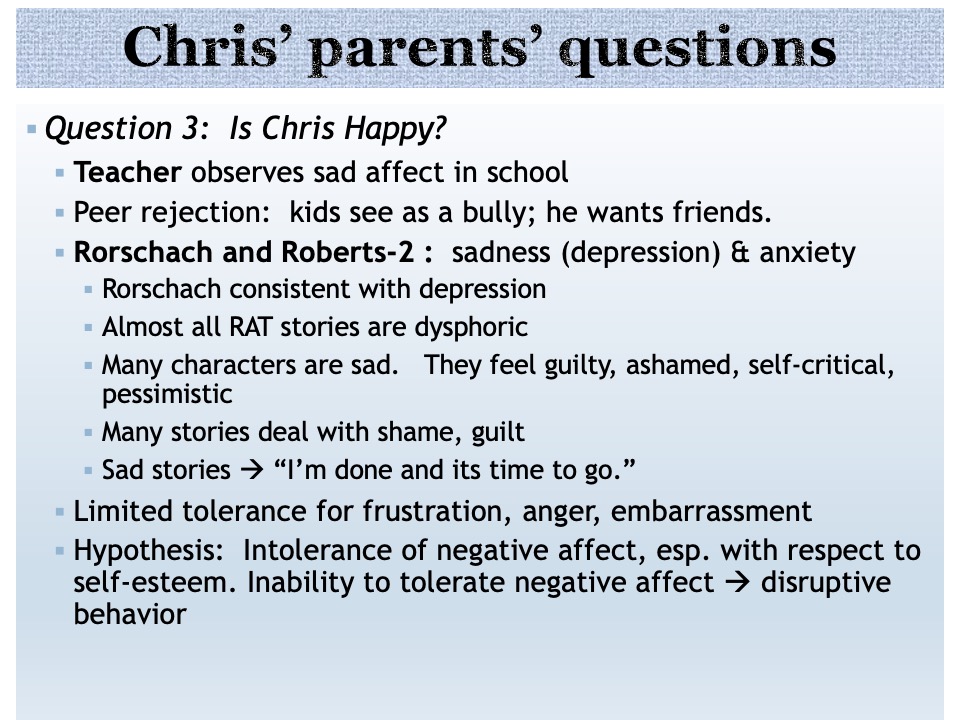

Question 3: Is Chris Happy?

- Teacher observes sad affect in school

- Peer rejection: kids see as a bully; he wants friends.

- Rorschach and Roberts-2 findings imply both sadness (depression) and anxiety

- Rorschach consistent with depression

- Roberts: Almost all stories are dysphoric; Many characters are sad. They feel guilty, ashamed, self-critical, pessimistic

- Many stories deal with shame, guilt

- Sad stories –> “I’m done and it’s time to go.”

- Chris displays an intolerance of sad affect, esp. with respect to self-esteem.

- One story: people are crying (next) “That I rule the world!”

- Teacher reported Brooding, seriousness

- Potential for peer rejection: kids see as a bully; he wants friends

- Inability to tolerate negative affect –> disruptive behavior

- Limited tolerance for frustration, anger, embarrassment

- Teacher observes sad affect in school

- Difficulty naming his feelings, especially angry feelings

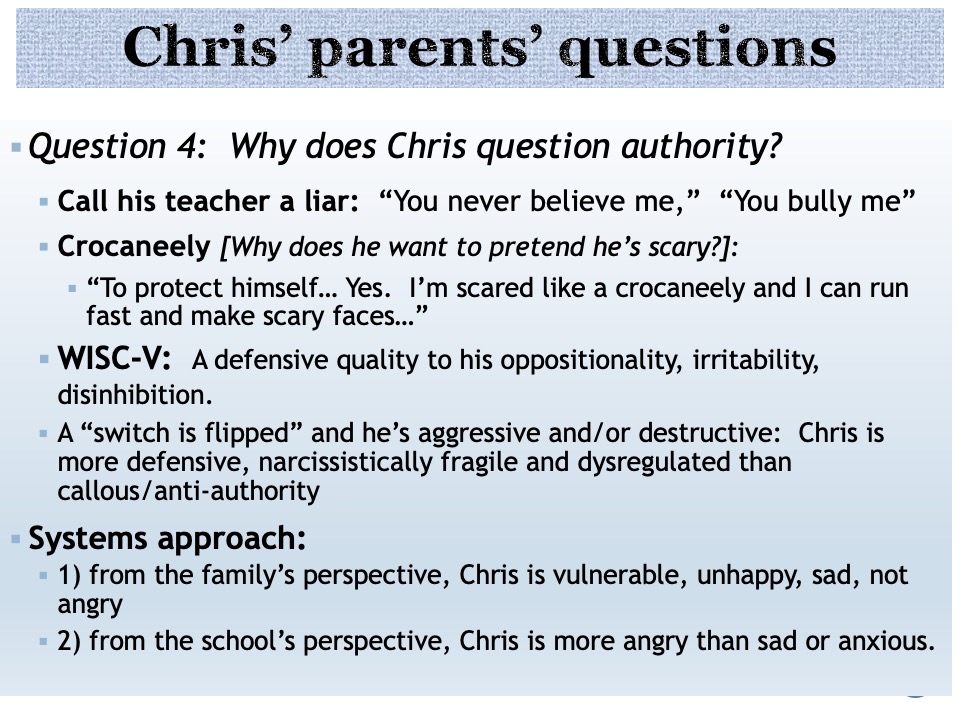

Question 4: Why does Chris question authority?

- He calls his teacher a liar, says “You never believe me,” “You bully me”

- In K he punched teacher in stomach, To principal: “Leave me alone, get out of here!”

When told this is unacceptable, says “Ok,” does it again. - Does not apologize, blames others, does not take responsibility

- The Crocaneely metaphor raises the question: “Why does he want to pretend he’s scary”

The metaphor suggests: because he’s scared: “To protect himself… Yes. I’m scared like a crocaneely and I can run fast and make scary faces…”

Consistent with this metaphor, his WISC-V behavior suggests a defensive quality to his oppositionality, irritability, disinhibition.

All the tests put together suggest that a “switch is flipped” and he’s aggressive and/or destructive: - Chris is more defensive, narcissistically fragile and dysregulated than callous/anti-authority

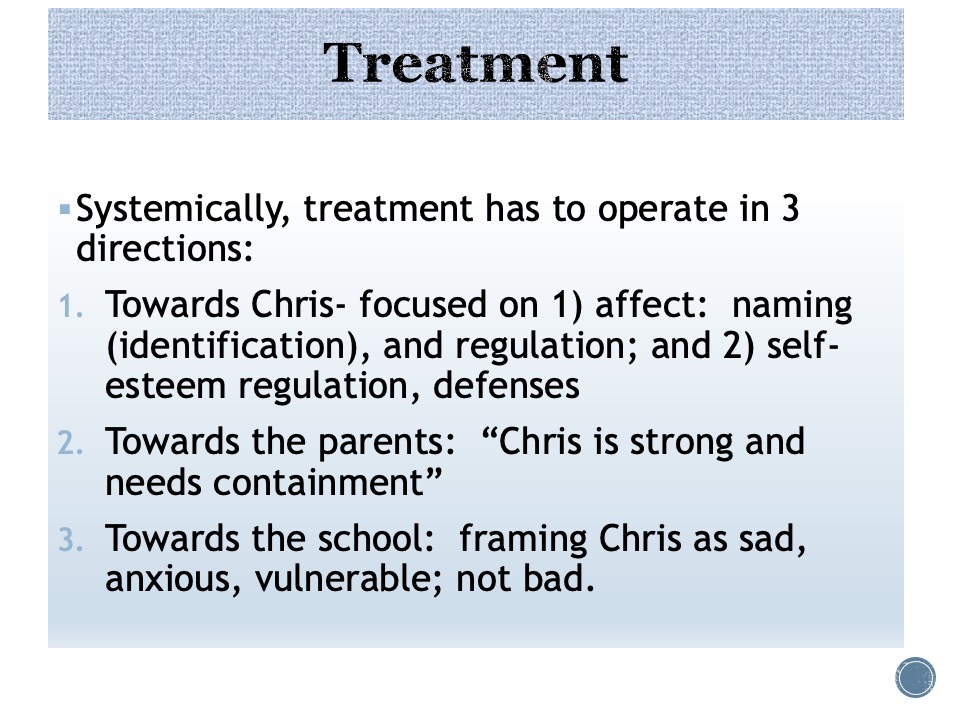

- Systems approach:

- 1) from the family perspective, Chris is experienced as vulnerable, unhappy, sad, not angry

- 2) from the school perspective, Chris is experienced as more angry than sad.

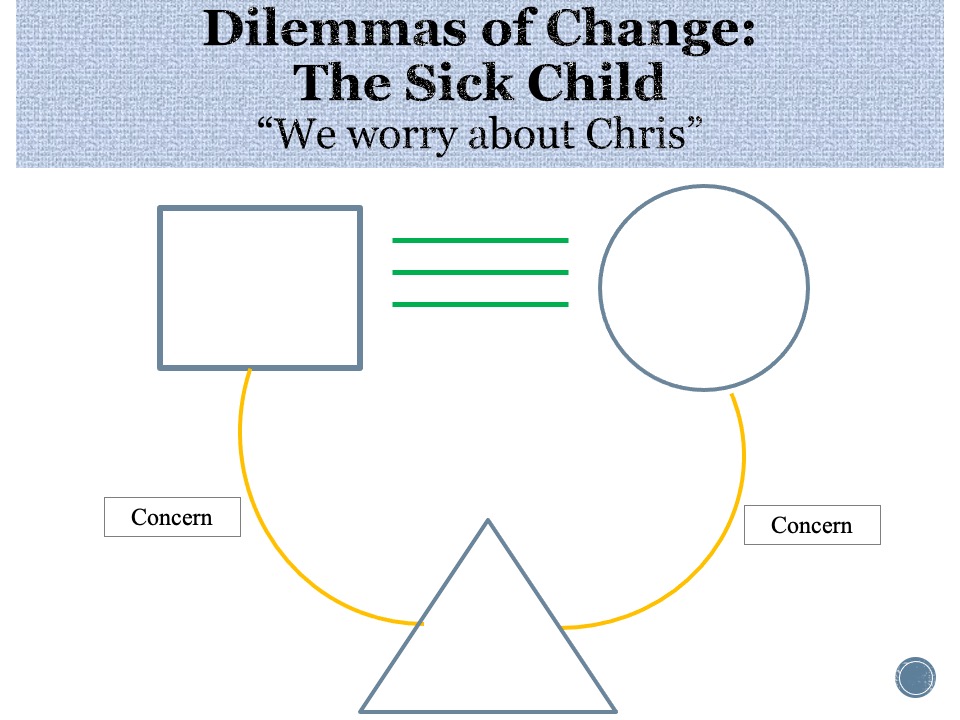

This is how Chris is perceived in his family:

- The sick child often shows underlying anger on psychological testing

- Parents are conflicted about expression of anger and either give mixed messages or fail to set appropriate boundaries

- If child begins to show anger, parents experience anxiety/terror

- The Goal is to reframe child from sick to “strong and needing containment”

This was one of the key messages during the parent feedback.

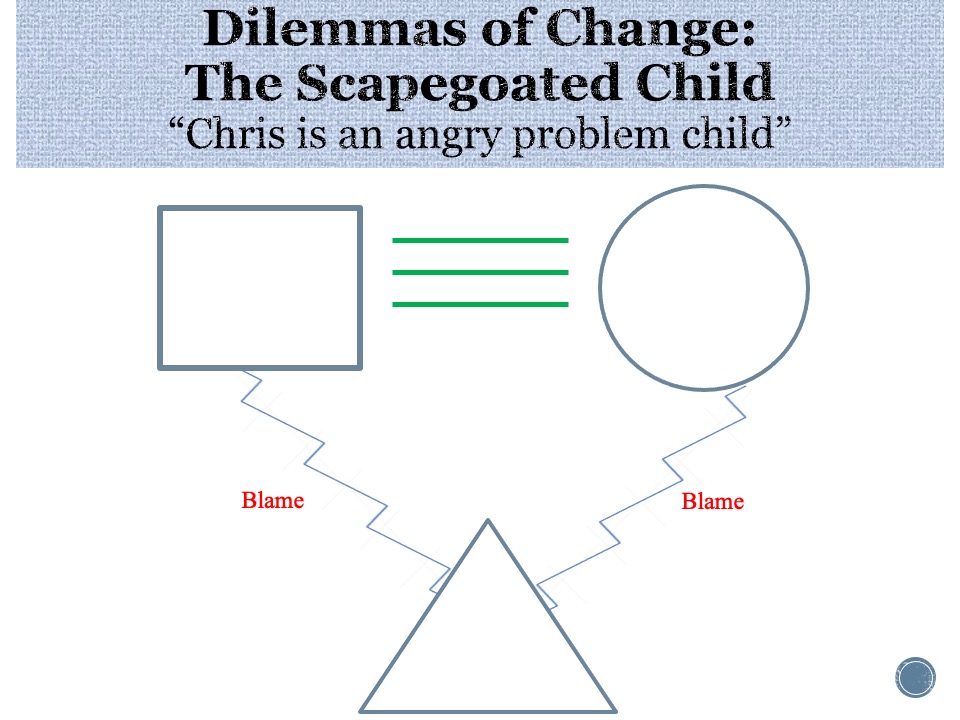

This is Chris, viewed from outside the family perspective: oppositional, defiant, disinhibited, angry and wild.

It is not true within the family, in this case

He can be seen as a bad boy (as he is by peers and their parents; thankfully not his teacher): Chris is a “problem child”

Typically, a scapegoated child seems depressed on psychological testing

Goal of TA is to reframe Chris, for the school from “bad” to “sad” and “anxious” I ended up meeting with the school and parents to discuss my assessment of Chris and to try to develop a new shared perspective on him.

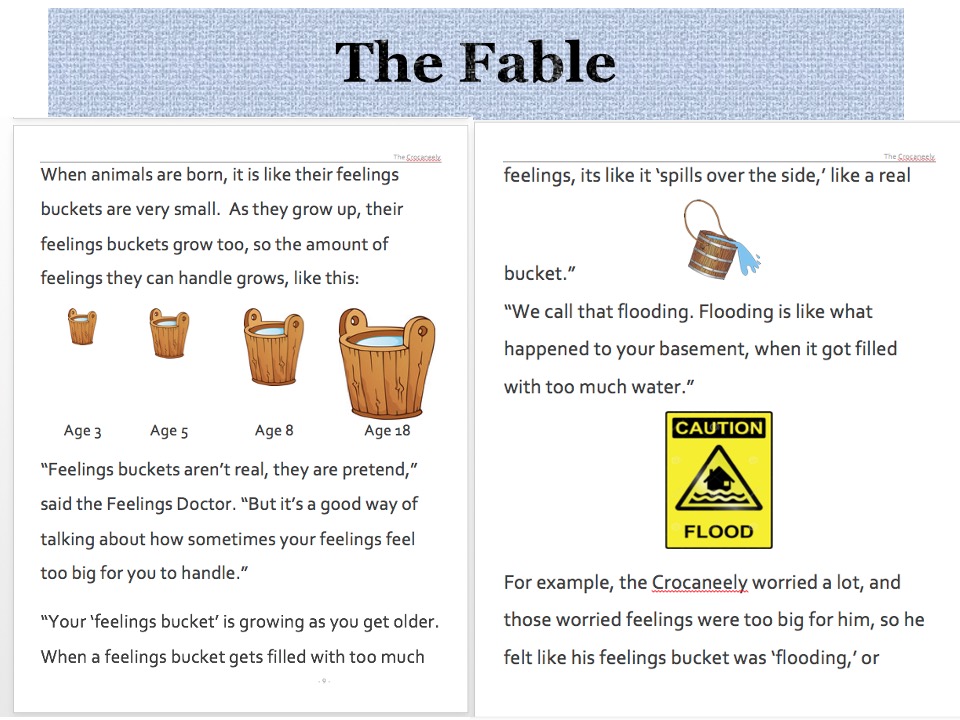

Jumping ahead to two pages that deal with self-regulation, flooding, and the use of therapy to grow one’s “feelings bucket”

The idea is to promote a therapeutic alliance between Chris and his therapist, and at the same time to choose

Mom and dad also received a formal report, based upon their assessment questions, their test results, and both their and the therapist’s comments during the summary feedback session.

As you can see, the WISC-V, and in this case observations of Chris while being administered the WISC-V, played an important role in a multi-method assessment designed to impart some therapeutic momentum, insight, reflection, and systemic changes.