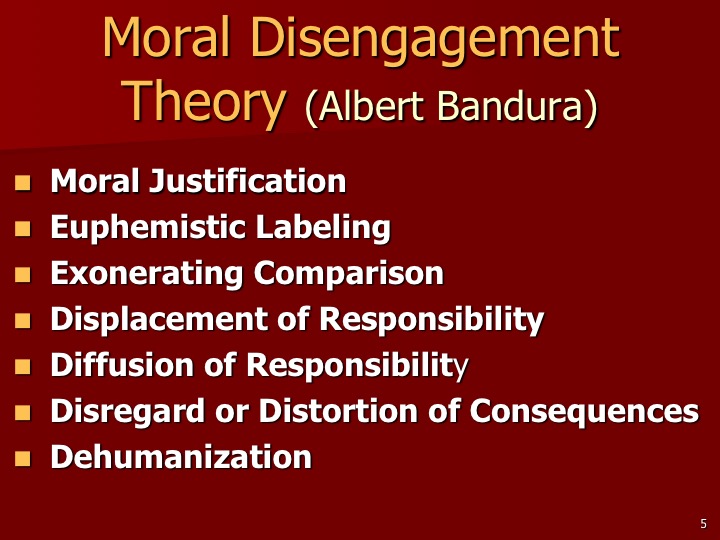

Moral Disengagement Theory

I want to introduce Moral Disengagement theory, which was developed by the social psychologist Albert Bandura. Moral disengagement theory attempts to explain how normal people become enemies, dehumanize others in order to fight, or kill, or mistreat them. How do normal people engage in immoral behavior? How do they get this past their consciences?

Think racism, terrorism, ethnic cleansing, war, and also high conflict divorce. But also think the tobacco and alcohol industries, toxic spills, gun manufacturers and arms dealers, and, in some cases political parties.

In war, for example, people become enemies, or targets, or subhuman, rather than individuals (human beings) we can hurt, with whose problems or pain we can empathize or want to help.

Let me make clear that what I am talking about is not psychopathology, but about the psychological mechanisms underlying a specific kind of immoral action.

How do normal people justify the treatment of others as objects, as enemies and targets? How do we square such mistreatment or abuse with our consciences? How do we disregard the harm we do to others, most significantly children?

Moral disengagement theory is the product of the developmental and social psychologist Albert Bandura.

Many of you are familiar with Milgram’s ‘obedience’ experiments. In Milgram’s paradigm experimental subjects were led to believe that they had administered electric shocks to other subjects when given orders to do so.

Bandura, in one of his many projects, elaborated on Milgram’s paradigm. In one study, he found that it was easier for a group than an individual to administer the intended shock.

In a variant of this experiment, the recipients of the punishment were described to the research subjects in either humanistic, animalistic or impersonal terms. Not surprisingly, when the victims’ human qualities were emphasized, they were treated more decently.

There are many social and psychological maneuvers, Bandura argues, by which moral standards and self-controls can be disengaged, resulting in inhumane conduct. What these mechanisms share in common is a process of blaming one’s adversaries and denial of responsibility.

Bandura described a number of mechanisms for moral disengagement. The key to this theory for our present purposes is that these mechanisms can operate in normal individuals as well as individuals with psychological disorders. What are the mechanisms of this moral disengagement?

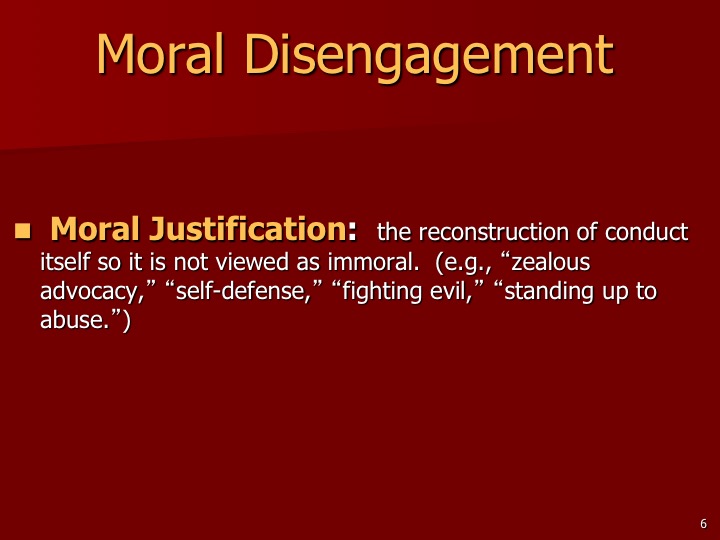

Moral Justification: is the reconstruction of conduct itself so it is not viewed as immoral

This is a frequent mechanism in war. We don’t turn people into dedicated fighters by persuading them to abandon their moral codes. Rather, we redefine the meaning of violence so that it can be done free of guilt. In this mindset, the victim needs to be punished for his past misdeeds.

We help people to see themselves as fighting, or bringing to justice, ruthless and evil oppressors- commies, Nazis, terrorists and the like- or as protecting their cherished values, saving humanity from subjugation and the like. Many atrocities have been construed as justified in a higher morality, even in religious terms.

In a custody case, a mother and her children tried to convince me that the ex-husband and father was a violent person, with whom the children should have as little contact as possible. His violence- let’s see, he once raised his hand during an argument, convincing his wife that he was going to strike her, so that she ran down the stairs in fright. In another ‘violent’ incident, he banged on the hood of her car to warn her against backing into the refrigerator in the garage. She and the kids sped off. She told the kids she was too afraid to spend the night at home. On a third occasion, the eldest son stepped in between dad and mom. He was sure dad was going to hit mom. That’s it. No one has ever been punched, or choked, or restrained by this man.

His children don’t talk with him when they are forced to see him. The way they treat him, he is their enemy. They don’t care about his feelings. They don’t believe he loves them and say they don’t love him. They are cold and distant towards him and his extended family. They say they want to stop seeing him altogether.

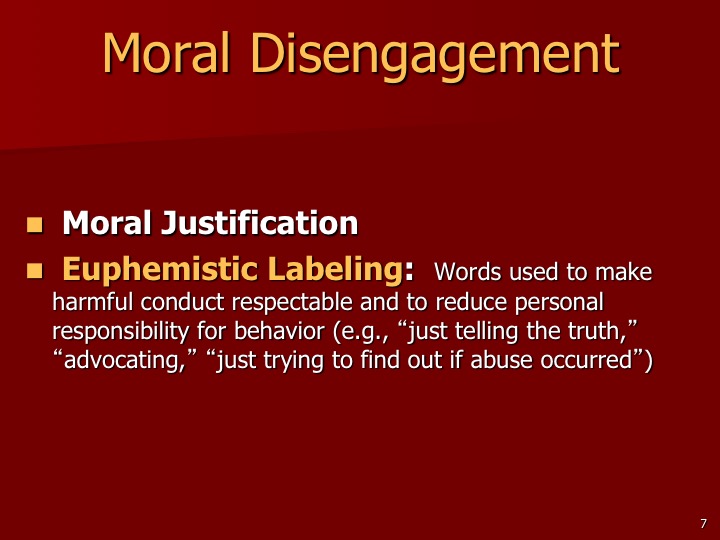

Euphemistic labeling: Is widely used to make harmful conduct respectable and to reduce personal responsibility for it: soldiers “waste” people rather than killing them, bombing attacks become “surgical strikes.”

In the family conflict arena “the truth” is the most common euphemistic label for providing information designed to do damage to someone else’s reputation or relationships.

The visit to the pediatrician or the call to CPS designed to elicit an abuse investigation shows a similar defense mechanism: “I wasn’t accusing anyone of anything. I was just trying to find out if this was true…”

I can’t tell you how many times attorneys have used the same kinds of euphemistic labels about their client’s foolish, wrongful or outrageous behavior.

The word “advocacy” is another common euphemism. A child therapist who offer opinions favoring one parent or the other in child custody cases is just an “advocate” for the child, in their own minds. Attorneys who have lost their moral compass often defend their “zealous advocacy” for their client.

A child therapist once talked about themes in the child’s symbolic play which had convinced her that the child was ‘intimidated’ by her father, and that dad’s parenting time should be reduced. In this child’s play “masculine” figures, such as dinosaurs, soldiers and cowboys acted in a violent and frightening fashion. ‘Had the child said anything specifically negative about his/her father?,’ I asked. The therapist seemed shocked that I asked such a ‘naïve’ question, failing to appreciate the “nature of child therapy. ” I am a child therapist, but I am extremely skeptical of using a child’s drawings, play, or other indirect means to assess a parent.

Exonerating Comparison: operates when our behavior is justified by the relatively worse behavior or immorality attributed to our adversary.

Terrorists, or freedom fighters, see their acts as ones of selfless martyrdom, when compared against the ‘cruel inhumanities’ perpetrated by their victims.

This mechanism is evident in the sometimes cruel treatment by children of parents from whom they are estranged, as described above in the case of the “violent” dad. Ask these children questions about their behavior, and you’ll get some interesting answers. For example, dad takes the children to church. At the end of the service the congregation offers each other the Peace of Christ. The children refuse to engage in this peaceful greeting to their father. Their rude behavior, they say, is ‘nothing compared to what he has done,’ his violent behavior.

In one case a child’s therapist called a father “sadistic” and recommended, based upon his self-assigned duty to advocate for his patient, that this father have only court-supervised contact with the child. He had met with this father on one or two occasions. A later psychological evaluation found no evidence of abuse or sadism or other personality traits which might endanger the child. But after 18 months with minimal contact, the relationship between father and son was very far gone.

A mother called a Licensing Board to accuse her ex-husband of a variety of misdeeds, in an effort to block his re-licensure as a physician. This was in spite of the fact that she was denying her children child support by blocking his effort to earn a decent living. She wasn’t trying to hurt him , she said, she was simply “sharing information (euphemistic labelling).” Later, she informed his employer in a different state that he had been convicted of domestic violence. How could I question this behavior, I was told, in light of what he had done in the past? He had abused her, she informed me (there had been an incident of mutual physical struggle).

The combination of moral justification, manipulation of language and exonerating comparison is a most powerful mechanism for disengaging moral control, Bandura argues. Not only is the aggressor spared self-criticism, guilt or shame. He or she can actually feel good about behavior which destroys the other person, or sabotages their relationship with the children.